Volume 21, Issue 2

June 18, 2020

ISSN 1099-839X

Shaping the Futures of Learning in the Digital Age

The STAC Model: Rethinking the Basic Functionality of Informal

Learning Spaces

Tom Haymes

Ideaspaces

Abstract: Productive “Third Spaces” are often an afterthought when designing learning

environments, both in a physical sense and online. These areas, properly mediated by technology

and designed around humans, can often be a key facilitator for student success. The STAC Model

is designed to provide a framework for understanding what makes these spaces successful in

capturing and retaining students who would otherwise leave the learning environment at the first

opportunity. STAC stands for “Stickiness, Toolsets, Adjacencies, and Community” and is an order

of priority system for prioritizing design and technological elements within any space. This article

describes the rationale behind the model and how it can be applied in both physical and online

environments.

Keywords: informal learning spaces, toolsets, human-tool interaction, hybrid learning, online

learning, learning spaces, learning management systems, conversational spaces, communities of

practice

Citation: Haymes, T. (2020). The STAC Model: Rethinking the basic functionality of informal

learning spaces. Current Issues in Education, 21(2). Retrieved from

http://cie.asu.edu/ojs/index.php/cieatasu/article/view/1915 This submission is part of a special

issue, Shaping the Futures of Learning in the Digital Age, guest-edited by Sean Leahy, Samantha

Becker, Ben Scragg, and Kim Flintoff.

Accepted: 6/14/2020

Current Issues in Education, 21(2)

1

The STAC Model

The STAC Model: Rethinking the Basic Functionality of Informal Learning Spaces

Every environment tells a story to its inhabitants. The story can be one of control or one

of empowerment. While both physical and online spaces are sometimes radically adapted to the

needs of their human inhabitants, their design sets a tone for the kinds of activity that can occur

in them. In a controlled classroom environment, a dynamic teacher can overcome some of the

limitations of the instructional space (although arguably he or she shouldn’t have to). In informal

environments this is not really possible. Students will walk with their feet if the space doesn’t

meet their needs. Informal spaces are where students see learning happening. Better students

model behavior to students who aren’t used to self-directed learning and behavior as well as

culture shift productively.

Informal spaces are an intersectional “third space” between students’ home/social lives

and their academic lives. As such, they form critical connective tissue between the more focused

learning environments they experience in the classroom and a tendency to leave school behind

when they leave the learning environment. These “hybrid” environments facilitate the creation of

communities of practice among the students. As Muller and Druin pointed out:

in such a hybrid space, enhanced knowledge exchange is possible, precisely because of

those questions, challenges, reinterpretations, and renegotiations. These dialogues across

differences and—more importantly—within differences are stronger when engaged in by

groups, emphasizing not only a shift from assumptions to reflections, but also from

individuals to collectives. (Muller & Druin, 2003, p. 1063, emphasis in original)

Frans Johansson makes a similar point in The Medici Effect when he argues that innovation

occurs in the intersections (Johansson, 2003). In other words, spaces “in between” are critical to

growth and learning. The trick is keeping students in these in-between spaces long enough for

groups to form.

If designed properly, a student-centric, empowered learning space can become a critical

tool for facilitating learning throughout the college, school, or online program. Jean Lave and

Etienne Wenger wrote in their classic Situated Learning, “learning is an integral and inseparable

aspect of social practice” (Etienne and Wenger, 1991, p. 31). All spaces in an environment need

to facilitate this social practice of learning, but none more so than informal spaces as, in addition

to the learning imperative, their very use is predicated on social norms. In an era when online

learning has become such an important modality, informal spaces have become even more

critical to success. For hybrid students a well-designed campus space can provide a critical

learning anchor for their online activity. Taking this to another level, the creation of wholly

online, student-informal environments could help bridge the engagement gap that is a serious

impediment to effective online learning.

At the beginnings of online learning, Diana Laurillard engaged in a deconstruction of

teaching and learning in an attempt to construct technological environments that would augment

teaching and learning. Obviously, online environments are technological environments, but

properly designed physical environments are also interfaces with technology and should follow

the same principles. All should be “productive” environments, which Laurillard describes as

including “microworlds, productive tools, and modelling environments” in which the learner can

“build something,” “engage with the subject,” and “learn how to represent these relationships in

some general formalism” (Laurillard, 2003, p. 171). All informal learning environments, both

online and in person, should aspire to be productive environments. Students will be drawn to

such environments, and they will form a critical backbone to their educational journeys.

Current Issues in Education, 21(2)

2

The STAC Model

Environments designed in this way have the potential to transform a billboard of information into

a community of learning.

Informal spaces should therefore be viewed as a set of learning tools. Tools must be

driven by their purpose and in this case the purposes are threefold (in order of priority): 1) Keep

students engaged and coming back to the space; 2) Provide modes of communication and

interaction; and 3) Expose students to a wider community of learning and opportunities. The

STAC Model is designed to prioritize these three kinds of “productive” engagement and align

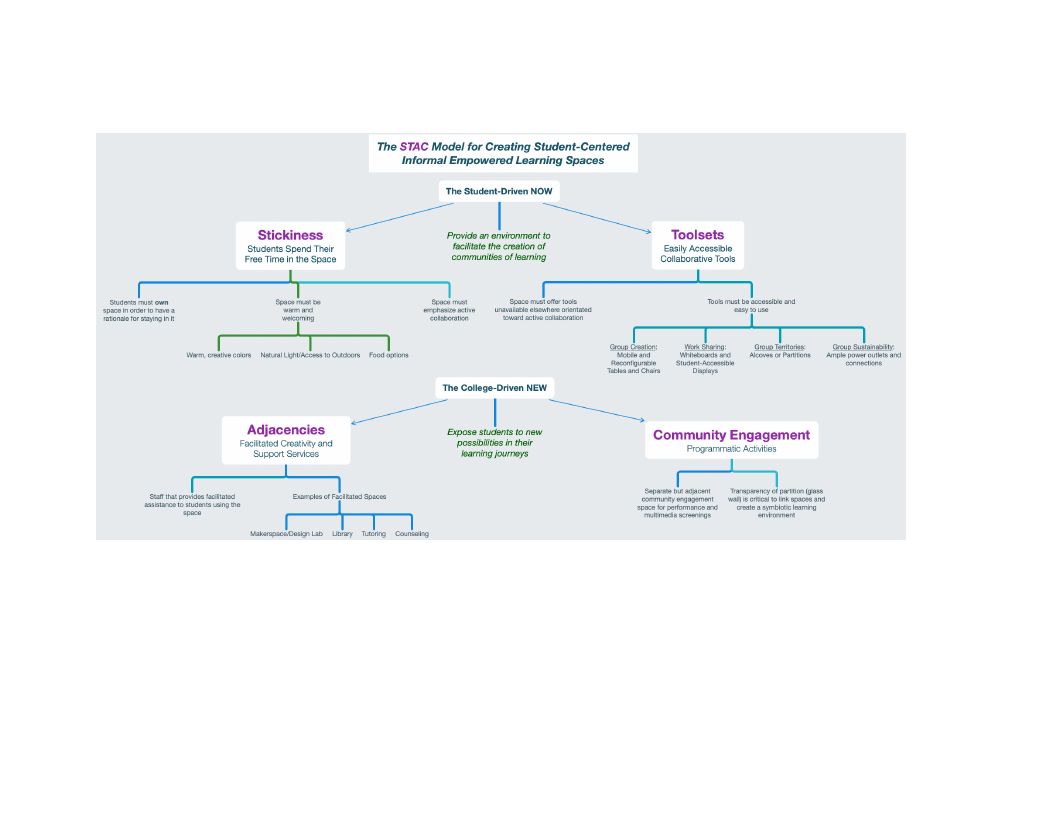

college services to support them. The four elements of the STAC model are, Stickiness, Toolsets,

Adjacencies, and Community Engagement. Together, they are designed to create an environment

that keeps students in the space and interacting with other students while exposing them to new

opportunities and resources designed to elicit curiosity and creativity.

The Holy Grail of informal learning spaces is the achievement of true peer-learning

environments. There is ample evidence to indicate that if you can get the students to pull together

toward their learning goals, then outcomes will dramatically improve. Residential campuses have

a distinct advantage in this area because the number of opportunities for social interaction on

campus grows exponentially when students also live there. Conversely, nonresidential campuses

often struggle with student interaction and, ironically, community-building, because students

tend to “visit” campus and then return to their “real” lives. Online “campuses” face perhaps the

greatest challenges in this area because of the interface between instruction, the design of their

technology, and the remoteness of the student experience.

Anything that keeps students interacting with peers longer has been shown to improve

learning outcomes. As Alexander Astin wrote over a quarter century ago:

The single most powerful source of influence on the undergraduate student’s academic

and personal development is the peer group. In particular, we found that the amount of

interaction among peers has far-reaching effects on nearly all areas of student learning

and development. (Astin, 1993, p. 7)

David Zandvliet notes, “[a] review of the eco-psychological literature similarly reveals a focus

on interpersonal and community factors that reflect value, fairness, respect, and collaboration.

This emphasis indicates the importance of community for environmental learning at both the

micro and macro levels” (Zandvliet, 2012, p. 127). The design and integration of informal spaces

into the overall learning mission of the institution is therefore critical.

The first level of the STAC model is designed to support student-centric needs now and is

driven by the need to facilitate productive peer interaction. The key to this level is the

development of community. As Lave and Wenger point out, “[t]he idea of identity/membership

is strongly tied to a conception of motivation. If the person is both member of a community and

agent of activity, the concept of the person closely links meaning and action in the world” (Lave

and Wenger, 1991, p. 122). Most undergraduates—particularly those challenged by the new

experience of college—struggle with the concept that they have some power over their own

learning journeys. An effective learning environment can provide a key bridge to linking

meaning and action in the world. The second level of the STAC Model represents the supporting

elements that the college provides to expose students to new opportunities and support. However,

if the needs of the first level are compromised by the second, the overall effectiveness of the

space will be substantially undermined. If students find the spaces to be unreliable places to

gather and are robbed of agency in the process, they are far less likely to stick in them.

Current Issues in Education, 21(2)

3

The STAC Model

Figure 1. The STAC Model for Physical Spaces. © 2019 Author

Current Issues in Education, 21(2)

4

The STAC Model

Designing Physical Spaces Using the STAC Model

Level 1 – The Student-Driven NOW

The fundamental rule of productive spaces is that they need to provide an environment

that is driven by the students first and foremost. If the students are deprived of agency, they are

unlikely to persist in the space, and/or they may find alternatives at the first possible opportunity.

The two basic levels of the STAC model are therefore fundamental to the success of any

productive space because they provide a rationale for being in the space in the first place and,

more importantly, a rationale for coming into the space and returning to it whenever possible.

Without these preconditions, any activities related to the second level will have to first overcome

the burden of creating an audience before anything programmatically new can even begin. These

are not facilitated spaces; they are facilitating spaces. The second-level spaces are where the

facilitation occurs. While having a complete suite of services available to students is the ideal

circumstance, if first-level criteria are met, the space will still be productive. The inverse is not

true. Consequently, second-level activities cannot be allowed to impinge on first-level functions

at the risk of ruining the student-centric logic of the space.

Stickiness: The space needs to provide an environment that is welcoming to students and

provides a rationale for them to stay on campus to work and interact with peers. The critical

aspect of this is that the students—within the bounds of reasonable safety and maintenance

considerations—should be able to reside in and reconfigure the space to meet their immediate

needs. The space should also accommodate longer-term occupancy and provide food services

where appropriate. Finally, the décor should reflect these priorities. The best way to get students

to congregate is to give this space a “clubhouse” feel where they know they can establish and

sustain their communities of practice.

Toolsets: The space needs to include easily accessible collaborative tools. These fall into

four functional categories:

1) Group Creation – Furniture must be mobile and reconfigurable to support a range of

group sizes up to 10 people. Tables and chairs on casters that can be easily combined

to create larger group sets are essential here. Round tables are generally to be avoided

because they dictate the size of the group.

2) Work Sharing – Whiteboards and student-accessible displays are critical to group

functionality. These should also be as mobile as possible throughout the space in

order to support different group locations. These tools should also provide a linkage

to digital tools such as concept mapping and file repositories.

3) Group Territories – Groups need to be able to establish temporary territories where

they can segregate themselves from other groups. There are at least two ways to

accomplish this. First, mobile partitions (which could also be writable surfaces such

as whiteboards) should be provided. A second option is to build alcoves into the

space where groups can congregate. The second solution is a bit more inflexible and

uses up edge space which might be better used to support adjacencies (see below).

4) Group Sustainability – There should be ample power outlets and other relevant

connections so that group cohesion is not dictated by battery life. Ubiquitous Wi-Fi is

assumed to be a part of the space as well to support access to online resources.

Level 2 – The College-Driven NEW

The second-level functions of these spaces are where the institution can make an impact

with its own agency. Part of college is exposing students to people and experiences that enrich

Current Issues in Education, 21(2)

5

The STAC Model

their skills or views of the world. That is fundamentally what level-two spaces are about. More

importantly than the spaces themselves, however, is the people that inhabit those spaces. Some

of these are regular staff who can expose students to new ways of learning or entirely new

disciplines. These spaces can also act as a conduit to the larger community outside the

institution. Using technology, these experiences can even be geographically unbound, such as

bringing in a remote speaker or facilitator via videoconferencing technology.

Adjacencies: Services that support student activity should be located adjacent to the

space and not in the space itself. These are staffed areas that may have more limited hours than

the main space. These spaces provide specialized capabilities and, more importantly, have

support staff who can assist students in exploring new things. Transparency is key to linking

these spaces to the central hub of informal learning. Some examples of adjacencies are:

1) Design Lab (Makerspace) – Making and design are increasingly important

skills in a world that we can increasingly shape to our needs. Students need to

learn the theory and practice of making throughout their academic careers. The

Design Lab is an accessible space for creating physical products that can range

from 3D printing to vinyl cutting to laser cutting. This should be a low barrier-to-

entry space that hosts periodic workshops on a variety of topics to include both

student requests and staff initiatives.

2) Library – Information and media creation services are another critical skill

modality for the 21st century. More than ever our students need support

navigating and creating media. The library is the logical place for this to occur as

librarians have always been stewards of information. Its role is to provide

information support to the space as well as tools associated with a Digital Media

Commons to complement the activities of the Design Lab in the creation of

digital products, such as videos, websites, etc.

3) Tutoring – A series of small rooms should be provided for tutoring support for

students. These rooms can be shared with the main space or the library for quiet

study or small group work when they are not staffed by tutors.

4) Counseling – Many students require emotional support and guidance during

their educational journeys. Having access to advisors and counselors can meet

critical needs that can often determine success or failure in school.

Community Engagement: This is a key intersectional space that can be used to provide

a venue for speakers, films, and other kinds of events. In addition to internal initiatives, it should

also be used as a key linkage to the outside community in order to expose students to the life of

the wider communities in which the school resides (geographical, academic, professional, etc.).

Like adjacencies, transparency should be provided to the greatest extent possible so that the

space can be visible from the main space without competing with it acoustically. This space

should be configured as a theater-like area with reconfigurable seating, a large display or

projector, and some sort of podium or stage for speakers. It should be acoustically insulated from

the larger main collaboration area.

Designing Online Spaces Using the STAC Model

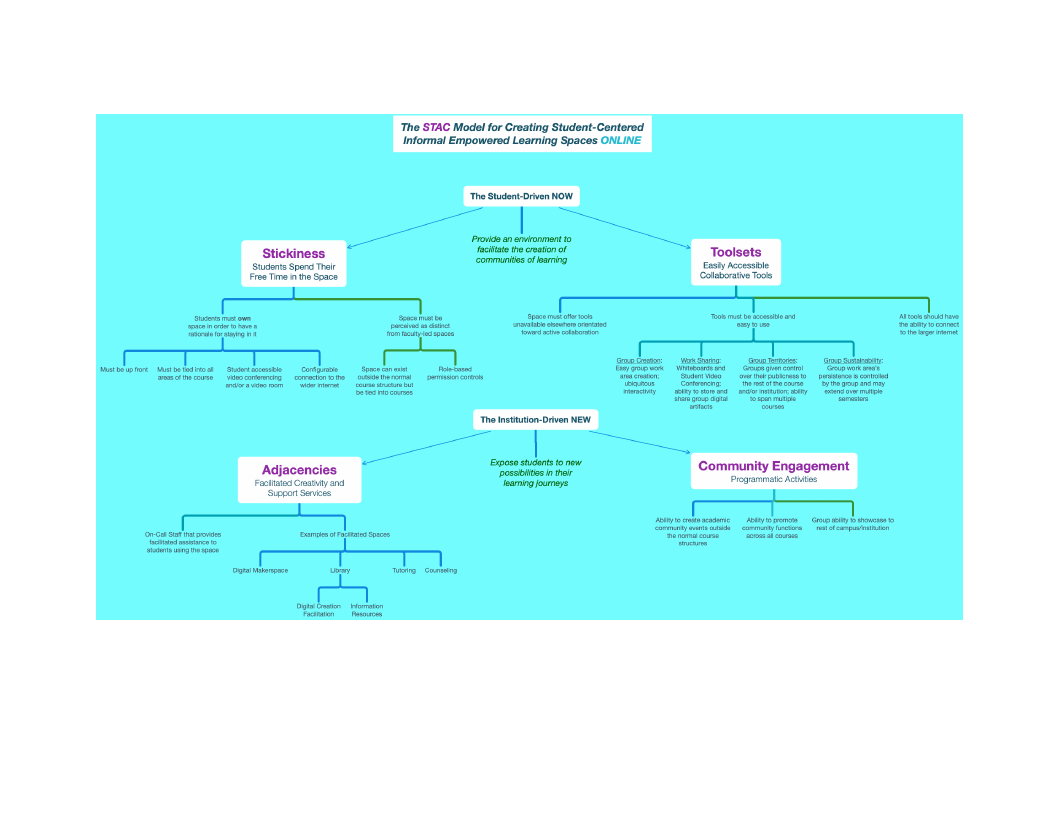

The same basic principles used in designing physical spaces can be applied to online

environments. Students studying in online environments need third spaces as much as, if not

more than, traditional students. This is because the transition space between “home” and

Current Issues in Education, 21(2)

6

The STAC Model

Figure 2. The STAC Model for Online Spaces. © 2019 Author

Current Issues in Education, 21(2)

7

The STAC Model

“school” is in many instances even more abrupt and porous. There is little incentive for students

to spend more than the minimum time necessary in learning environments when they are literally

sitting in their home environments in many instances. However, as was noted in the introduction

to this article, it is critical for their success that they spend as much time interacting with virtual

learning environments as possible. This will simply not happen without a “sticky” informal

environment that exists between and above the formal environments represented by the

“classroom” spaces.

The STAC Model avoids the McLuhanesque mistake that characterizes many online

environments by focusing on the underlying purposes of any space instead of simply replicating

functionalities that might work in a physical environment into a virtual one. Effective learning is

universal. Its modalities aren’t. If you understand why you are designing a space the way that you

are, it is possible to create new kinds of online spaces and identify areas of opportunity that

augment the human capacity for learning using the tools made available by the disconnection

from space and time that online networks offer us.

Level 1 – The Student-Driven NOW

Students have often been viewed with a level of suspicion in online spaces. There seems

to be far more discussion of controlling the environment because of fears such as cheating or

electronic vandalism than there is of student agency in online environments. It’s no accident,

therefore, that students often perceive their learning environments as being uninviting places to

spend their hours online. The logic for level-one spaces remains the same in an online

environment even as its realization becomes even more challenging. If we don’t want students to

log on, go to their class spaces, and do the minimum necessary before logging off, then

consideration must be given to designing student-centric spaces that are at least partially under

student control.

Stickiness: To the extent possible students must feel that they have ownership and

control over their online congregation spaces.

1) Sticky spaces need to be very obviously accessible throughout any course as this

environment will be unexpected to most students.

2) On-demand videoconferencing or other interactive modalities (think Fortnite without

the shooting) can be used to facilitate a club-like atmosphere.

3) These spaces must have the capability to seamlessly integrate with their existing modes

of online social interaction such as Twitter, Instagram, or messaging.

Toolsets: The environment needs to include easily accessible collaborative tools. These

fall into four categories:

1) Group Creation – Group spaces must be easy to form from a wide variety of areas in

the online environment.

2) Work Sharing – Groups should have access to a range of shared interactive tools such

as digital whiteboards, concept mapping, and student videoconferencing on demand, in

addition to a mechanism for storing and sharing files.

3) Group Territories – Groups need to be able to define their digital territories. This

means that they need to be able to control the publicness of their group activities from

the rest of the institution (subject to administrator override). Group spaces should also

have the capacity to span multiple courses and even be disconnected from any online

course registration at all.

Current Issues in Education, 21(2)

8

The STAC Model

4) Group Sustainability – Groups should also be able to control the persistence of their

online spaces, extending even beyond the bounds of a given semester or even

graduation. While limits will probably need to be placed on this capability there is

benefit in extending learning beyond the traditional boundaries of classroom instruction

and even to bringing in non-student members such as community members and

mentors.

Level 2 – The Institution-Driven NEW

The online environment provides interesting and—for the most part—unexplored

possibilities for experience and support facilitation. With the right tools, staff and faculty could

fairly easily devise online experiences for students divorced from the need for a physical

infrastructure. Online tutoring and counseling are perhaps the most developed in this area, but

other environments have real potential to transform the online student experience.

Adjacencies: Services need to be packaged with the student experience. The key

distinguishing factor of these elements is that they are staffed (and consequently may have more

limited hours than other spaces within the LMS). These spaces need to be accessible from

anywhere within the LMS environment and to be readily apparent to student users to be

effective.

1) Digital Makerspace – As in the physical environment, the core of this experience

needs to be centered around making and design. There are a number of interesting

virtual possibilities that might support these modalities. Perhaps this could be a

hackerspace with digital programming tools that allow students to build coded creations

rather than physical artifacts. Another possible model for this would be to create an

online design studio with remote 3D printing where students could go into a lab and

pick up their products at their convenience. In either case, the staff should be well-

versed in the design process and should offer periodic workshops in design and

prototyping as they would in a physical space.

2) Library – In many ways the online library resembles the physical space more closely

than most other environments. This is not surprising in that media has become

increasingly disconnected from its physical manifestations. Library staff should provide

information support via videoconferencing to the environment. Media tools associated

with a Digital Media Commons can complement the activities of the Digital

Makerspace in the creation of digital products such as videos, websites, and others. The

staff would give periodic synchronous and asynchronous workshops on strategies for

effective research and communication.

3) Tutoring – Online tutoring services are a critical part of the support package.

Synchronous and asynchronous modes should both be supported in this area. This

would also be a logical place for workshops on student success strategies.

4) Counseling – In a physical environment, it makes sense to place counseling services

(ADA, course planning, and psychological) in a separate area, but online there is a logic

to proximity because students are more likely to struggle in finding these kinds of

resources, and privacy is defined much differently if physical proximity is a nonissue.

As such, counseling and related student services need to be digitally “adjacent” to all

areas of the online learning environment in order for them to be apparent to the student

users.

Current Issues in Education, 21(2)

9

The STAC Model

Community Engagement: All of these online environments need to have a built-in tool

to create online events where speakers and other events can be broadcast to the larger community

rather than within the “walls” of a single course. These tools must be easily accessible and

ubiquitous to administrators and faculty wishing to reach out to the larger community. This is

actually easier in an online environment as speakers can be remote and the usual physical

limitations of room size can be eliminated altogether (although organizers should still have the

ability to manage group sizes for interactive reasons).

Designing Environments that Create Community

By drilling down to the basic principles of what the environment is intended to provide,

we can establish a set of priorities centered on student empowerment and engagement. At a

minimum, any effective informal space must cover the individual needs of students in the STAC

Model (stickiness and toolsets) to create an environment where students will willingly

congregate. Most of the cost and complexity of this space is associated with institutional-level

learning support activities (adjacencies and community engagement).

Finally, and most importantly, STAC must form the basis for the management of the

environments, both online and in person. Environments can facilitate desired activities. They do

not in themselves create those activities. They must be managed according to the priorities of the

STAC Model, giving student empowerment and access to tools priority over all other activities

in the environment. Informal spaces are, by their very nature, fragile environments, often

occupied by students who are unsure of how to make maximum use of them. Attempts to control

these spaces can easily disrupt these tentative explorations of what it means to be a lifelong

learner and diminish the overall dynamic of the campus or online platform as an effective

learning environment. That is not the story we want our learning spaces to tell.

References

Astin, A. W. (1993). What matters in college? Liberal Education, 79(4), 4-16.

Johansson, F. (2006). The Medici effect: What elephants and epidemics can teach us about

innovation. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Laurillard, D. (2003). Rethinking university teaching: A framework for the effective use of

learning technologies. New York: Routledge.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Muller, M. J., & Druin, A. (2003). Participatory design: The Third Space in HCI. In J. A. Jacko

& A. Sears (Eds.), The human-computer interaction handbook: Fundamentals, evolving

technologies and emerging applications (pp. 1051-1068). Hillsdale, NJ: L. Erlbaum

Associates.

Zandvliet, D. B. (2012). Development and validation of the Place-Based Learning and

Constructivist Environment Survey (PLACES). Learning Environments Research, 15,

125-140.

Current Issues in Education, 21(2)

10

The STAC Model

Tom Haymes

Ideaspaces

Author Notes

Guest Editor Notes

Sean M. Leahy, Ph.D.

Arizona State University, Director of Technology Initiatives

sean.m.leahy@asu.edu

Samantha Adams Becker

Arizona State University, Executive Director, Creative & Communications; Community

Director, ShapingEDU

sam.becker@asu.edu

Ben Scragg, MA, MBA

Arizona State University, Director of Design Initiatives

bscragg@asu.edu

Kim Flintoff, M.Ed MACEL

Curtin University, Learning Futures Advisor

K.Flintoff@curtin.edu.au

Current Issues in Education, 21(2)

11

The STAC Model

Volume 21, Issue 2

June 18, 2020

ISSN 1099-839X

Readers are free to copy, display, and distribute this article, as long as the work is attributed to the

author(s) and Current Issues in Education (CIE), it is distributed for non-commercial purposes only, and no alteration

or transformation is made in the work. More details of this Creative Commons license are available at

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/. All other uses must be approved by the author(s) or CIE. Requests

to reprint CIE articles in other journals should be addressed to the author. Reprints should credit CIE as the original

publisher and include the URL of the CIE publication. CIE is published by the Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College at

Arizona State University.

Editorial Team

Consulting Editor

Neelakshi Tewari

Executive Editor

Marina Basu

Section Editors

L&I – Renee Bhatti-Klug

LLT – Anani Vasquez

EPE – Ivonne Lujano Vilchis

Review Board

Blair Stamper

Melissa Warr

Monica Kessel

Helene Shapiro

Sarah Salinas

Faculty Advisors

Josephine Marsh

Leigh Wolf

Current Issues in Education, 21(2)

12