Volume 22, Issue 1

January 7, 2021

ISSN 1099-839X

Shaping the Futures of Learning in the Digital Age

Self-Mapped Learning Pathways: Theoretical Underpinnings and

Practical Course Design for Individualized Learning

Matt Crosslin, PhD

Orbis Education

Abstract: In the Fall of 2014, several universities came together to offer a unique “dual-layer” open

online course. This course was designed with two complete layers from two different course design

modalities (instructivism and connectivism). Learners were granted the freedom to create an

individualized pathway through the course involving either layer, both layers, or a custom

combination of both layers at any given point in the course. Since these options gave learners the

ability to map their own pathway as a learning process, this course structure is now referred to as

Self-Mapped Learning Pathways. The goal of this design methodology is to allow for true

individualization of the learning process for each learner. This article will examine the theoretical

underpinnings of Self-Mapped Learning Pathways design methodology. Additionally, several

design considerations will be suggested based on practical application as well as research results.

Keywords: Heutagogy, Learner Agency, Individualized Learning, Learning Theory, Instructional

Design, Open Learning, Student-Centered Learning, Gamification, Learning Pathways

Citation: Crosslin, M. (2021). Self-mapped learning pathways: Theoretical underpinnings and

practical course design for individualized learning. Current Issues in Education, 21(2). Retrieved

from http://cie.asu.edu/ojs/index.php/cieatasu/article/view/1900 This submission is part of a

special issue, Shaping the Futures of Learning in the Digital Age, guest-edited by Sean Leahy,

Samantha Becker, Ben Scragg, and Kim Flintoff.

Accepted: 10/27/2020

Introduction

While the world of education is constantly fluctuating, one concept that seems to remain

constant is that the design of many courses is based on a single pre-determined pathway through

Current Issues in Education, 22(1)

1

Crosslin: Self-Mapped Learning Pathways

the course content. This pre-determined pathway could be an extensively controlled one, or a

pathway that is somewhat loose in its structure. Either way, course pathways are generally tied to

a design where the learner does what the instructor thinks they need to be doing at any given

moment in the course (Onyesolu et al., 2013). Some courses do venture outside of this instructor-

guided format and into adaptive/personalized learning or social learning. However, most adaptive

or personalized learning designs are really just a set number of pre-determined pathways through

course content with situated choices leading to the different pre-determined pathway options

(Basham et al., 2016). Additionally, some learners – especially those that are accustomed to

following the instructor’s predefined pathway through a course – may find social learning too ill-

structured.

Many see learning as an “either/or” proposition: either one follows the instructor and learns

from a more knowledgeable other, or one forges their own path through social connections and

self-determined learning (Porcaro, 2011). The reality may be that many learners need both at

different times for different topics or skills (Anders, 2015; Bain, 2003). Sometimes learners need

to sit down and follow what the experts prescribe as a pathway to learn a new skill, and other times

learners need to find their own way by connecting with other humans or even machines (like the

Internet). These different ways of interacting with instruction could be referred to as modalities of

learning: one modality being “instructor-focused” and the other modality being “learner-centered.”

However, designing one course that meets either modality is a difficult undertaking, as any

instructor or instructional designer can attest. Designing a course that meets more than one

modality might seem impossible, but what if it actually wasn’t? The Self-Mapped Learning

Pathways model, based on the concept of customizable modalities, is a new paradigm that attempts

to create a design methodology that allows learners to choose their own learning modality at any

point in a course. The overall effect of a course designed in this paradigm is that each learner self-

maps their own custom pathway through course material.

This design methodology is important due to the increasing number of universities

attempting to reach more diverse populations, especially in online courses (Rovai & Downey,

2010). Globalization and integration has created a much richer set of socio-culturally diverse

contexts in education. Additionally, even within traditionally consistent groupings such as

ethnicity there are still differences based on socioeconomic status, geographic location, familial

connections, access to technology, and many other factors. Assuming that all learners in any given

course will all be “on the same page” as far as prior knowledge, pre-existing skills, and educational

interests is less possible than ever before. Self-Mapped Learning Pathways is not only a

methodology, but also an epistemological mindset that seeks to open up learning pathways to allow

the learner to become the final design agent in the personalization process.

Overarching Theoretical Concepts

Before diving into the principles of design and power dynamics that form the foundation

of Self-Mapped Learning Pathways design, a brief examination of over-arching guiding theoretical

concepts is in order. The first of these concepts has already been mentioned: sociocultural theory.

Although sociocultural theory is a complex idea based on the work of Lev Vygotsky, the

foundational idea to focus on for this methodology is how individual learners have different

fluctuating contexts (cultural, institutional, historical, etc) that variably influence their mental

states and social interactions at any given time (Dosunmu, 2013). For the purpose of the design

methodology covered in this paper, self-mapping of learning pathways allows learners from

different sociocultural groupings to occupy the same learning experience without being forced to

Current Issues in Education, 21(2)

2

Crosslin: Self-Mapped Learning Pathways

adjust their learning expectations to the specific sociocultural context of the instructor or other

learners (unless they choose to do so in order to meet their personal learning goals).

As far as the main guiding principles for this design methodology, the work of Gayatri

Chakravorty Spivak in Can the Subaltern Speak? serves as basis for the two main issues to consider

with Self-Mapped Learning Pathways. Spivak (1988) looked at the work of many post-colonialists

in India and pointed out that they were mostly speaking for subalterns, rather than letting subalterns

speak for themselves. Additionally, Spivak had concerns that many were looking at subalterns as

one homogenous group that all had one voice, instead of as a diverse group of different people

with different points of view. While learners would not be considered “subaltern” in Spivak’s work

(de Kock, 1992), the foundational idea (inspired by her work) of allowing learners to speak for

themselves because there is no assumption that they all have the same needs (or even one opinion

or preference for how they learn) serves as a guiding principle for Self-Mapped Learning

Pathways. For example, when instructors force all learners into “student-centered learning”

without letting students have a say if they want that or not, this assumes that all learners need

student-centered learning at that moment and that the instructor gets to determine that modality for

all.

Because of these guiding principles, this methodology needs a more empowering

epistemology such as heutagogy. Heutagogy is a field of study that focuses on self-determined

learning, where learners are taught how to learn rather than what specifically to learn (Blaschke,

2012; Hase & Kenyon, 2007). Self-Mapped Learning Pathways is a design methodology that was

conceptualized as one way to move towards self-regulated learning, allowing those that are ready

to self-determine to do so, while also providing scaffolding for other learners that are on their way

to becoming self-determined in their learning.

One important practical application concept that guides Self-Mapped Learning Pathways

is gamification. While the process of mapping a learning pathway could itself be considered a

game due to factors like uncertainty, goal-orientation, decision-making, involving special social

groups, and making a process of activities (Salen et al., 2004), gamification as defined as “the use

of game elements in non-game contexts” (Dicheva et al., 2015, p. 75) is a better frame of reference

here. While it would be possible to make many learning pathways courses into full games, not all

course topics would be suited to become actual educational games. However, as will be explored

in this article, gamification concepts like freedom of choice, multiple routes, onboarding, new

roles, freedom to fail, customization, and social engagement loops (Dicheva et al., 2015) are core

elements of designing a Self-Mapped Learning Pathways course.

The final concept to cover is metamodernism. Metamodernism is a proposed successor to

postmodernism that attempts to describe how culture is shifting towards a mindset that embraces

elements of modernism and postmodernism at the same time, in a way that is similar to both, but

also goes beyond both (Vermeulen & Van Den Akker, 2010). Metamodernism is a way of

approaching the world that “negotiates between a yearning for universal truths on the one hand

and an (a)political relativism on the other” (Luna, 2016, para. 4). This concept sets the stage for

self-mapping, in that learners and instructors realize that their personal pathway might be the best

for them, but not the best pathway for others.

Principles of Design in Creating Customizable Pathways

The biggest concept to understand in creating a self-mapped pathways course is that the

goal of the design is to expose the underlying power and control dynamics beneath various

instructional modalities, thus allowing the learner to understand the choices that must be made in

Current Issues in Education, 21(2)

3

Crosslin: Self-Mapped Learning Pathways

customizing their own pathway. For example, traditional instructor-led courses are designed in a

manner than places most of the power and control of a course in the hands of the instructor. This

might be a good option for some learners at some points in the course, but not for all learners for

the entire duration of the course or even for individual learners at all points in the course. Due to

varying sociocultural factors as well as differing levels of pre-existing knowledge, different

learners will have different educational modality needs at different points in the course – with each

pattern of need being unique from the others. Additionally, individual learners could have

constantly changing needs for varied modalities based on anything from lack of sleep to emotional

stress.

The typical design structure in most courses has been to create one pathway through the

content that all learners must follow. This pathway may be linear or not: it could contain situated

choices or variable pathways as the course progresses, but all of those options are still pre-

prescribed paths in most cases. Traditional courses also might contain direct instruction, social

learning, group work, or other forms of less structured pathways; however, these design

methodologies are often predetermined by the instructor to be for all learners regardless of any

other factors. For example, when all learners in a course are put into groups whether they need

social learning for the topic at hand or not.

The major shift that is made with Self-Mapped Learning Pathways design is that the learner

becomes a co-designer in the learning experience. The learner will determine what modality they

utilize at any moment in the course. If a learner feels that the topic for the week is new to them

and they need to follow a linear prescribed pathway, they can do so. If the learner feels they have

a decent grasp of the topic but need to explore a less structured social learning pathway to look at

how to apply the topic to their life, they can take that pathway. If they feel that the topic does not

really connect with their particular sociocultural contexts in learning, they are free to create that

pathway.

Power Issues in Education

How is this design methodology situated in the general concepts of power and control in

education? Power and control are two concepts that are basically a part of all areas of life.

However, creating a consistent definition of power has proven difficult for theorists and

researchers alike, due to most researchers focusing on definitions for their specific research study

(McLeod & Lin, 2010). For the purpose of this paper, the definition provided by Yukl (2006) will

suffice: “the capacity of one party (the agent) to influence another party (the target)” (p. 146).

Foucault (1980) described the issue of power in this manner:

…in any society, there are manifold relations of power which permeate,

characterize and constitute the social body, and these relations of power cannot

themselves be established, consolidated nor implemented without the production,

accumulation, circulation and functioning of a discourse. (p. 93)

Education is one part of our society that is involved with the production, accumulation, circulation,

and functioning of a communicative discourse. Many educators and researchers are seeking to

“understand human communication as a universal means to comprehend the social world” (Warren

& Wakefield, 2012, p. 100) because “this communication and related academic principles are the

core of social research and educational theory” (Warren & Wakefield, 2012, p. 100). The nature

Current Issues in Education, 21(2)

4

Crosslin: Self-Mapped Learning Pathways

of who is producing this narrative as well as who is accumulating and circulating it is one of the

key foundations of power issues in education.

Habermas (1971) further connected power and control with education and knowledge with

his concepts of the three kinds of knowledge: instrumental, communicative, and emancipatory.

Instrumental knowledge is the basic knowledge that all humans need in order to survive and

possibly control and self-regulate their own environment. In terms of Foucault’s statement above

on power in society, this would be the establishment and accumulation of power. Communicative

knowledge is based on the ability to interpret, engage with, and negotiate understandings of the

world around us. Again, in terms of the statement Foucault made on power, this is the circulation

and functioning of discourse. Finally, emancipatory knowledge is a process that critically

questions not only ourselves, but also the social systems of society. This type of knowledge would

seem to be outside of Foucault’s boundaries of relations of power. However, Foucault (1980) did

conclude

If one wants to look for a non-disciplinary form of power, or rather, to struggle

against disciplines and disciplinary power it is not towards the ancient right of

sovereignty that one should turn, but towards the possibility of a new form of right,

one which must indeed be anti-disciplinarian, but at the same time liberated from

the principle of sovereignty. (p. 108)

Critically questioning ourselves as well as society around us could be one way to become anti-

disciplinarian as well as liberated from the sovereign control of others. This could also be another

avenue to self-regulate our learning and existence. Therefore, the three forms of knowledge that

Habermas (1971) describes (instrumental, communicative, and emancipatory) can be seen as a

good framework for describing power relationships and control in education.

Instrumental Knowledge and Power

To that end, the first form of knowledge to examine is instrumental. This type of knowledge

is probably the most familiar form in education, as it is most closely aligned with instructivism.

Instructivism is a broad learning theory that basically “assumes the effectiveness of passive

reception of sanctioned information through memorization and recall" (Porcaro, 2011, p. 40).

Within this broad framework falls the behaviorism of Skinner and Thorndike as well as the

cognitivism of Gagne and Bruner. The main connective strand for these diverse ideas is that

“instructivists, whether behaviorist or cognitivist, are ontologically objectivist and realist, and

epistemologically empiricist…. they see learning as simply mapping the real, external world onto

the minds or behaviors of the student” (Porcaro, 2011, p. 41). This means that the power to regulate

learning and engagement rests outside of the learner – usually with an expert instructor or expertly-

programmed set of media – and therefore those with the knowledge have established power and

control that must be accumulated by a learner that is dependent upon a more knowledgeable,

powerful other.

Other words used to describe instructivism are objectivism and institutionalism (Onyesolu

et al., 2013). Whatever the term that is used, the idea is still seen as a way to transfer knowledge

into the brain of the learner in order to change behavior. According to Onyesolu et al. (2013), this

method is the lecture model of instruction that is commonly utilized by 70-90% of university

professors. What this means for higher education is that most instructors design themselves as the

seat of power for the courses that they teach in some fashion. It would also mean that they are

Current Issues in Education, 21(2)

5

Crosslin: Self-Mapped Learning Pathways

probably most likely transmitting instrumental knowledge designed to help learners survive and

control their environment. But a major issue that arises is that this means all learners are seeking

to survive and control (or regulate) their environment, opening the door for possible conflicts of

interest between learners. Other forms of knowledge and power are needed to bring these

competing agendas to a place of peaceful co-existence.

Communicative Knowledge and Power

The next form of knowledge to examine more in depth is communicative. This type of

knowledge is also probably familiar to many in education, as it is most closely aligned with

constructivism. Constructivism is a diverse learning theory that displays “a variety of ontological

and epistemological perspectives" (Porcaro, 2011, p. 41). These varied perspectives include the

cognitive constructivism of Piaget (which is almost cognitivism) as well as the sociocultural

constructivism of Vygotsky. Despite the wide coverage of perspectives, the unifying strength of

constructivism is that it is “well-suited for teaching the epistemic practices and collaborative

problem-solving skills necessary in a knowledge society while empowering learners through

democratic participation in learning and dialogue” (Porcaro, 2011, p. 43). Onyesolu et al. (2013)

clarified this diverse perspective by defining it as a theory that is “rooted in the idea that the learner

actively constructs his knowledge, not that it is passively acquired from without” (p. 40). This

means that the power rests inside of the learner – usually with each learner bringing their unique

perspective to a negotiation of learning – and therefore those with the knowledge have the role of

sharing knowledge with those who don’t, with the goal being to come to a shared understanding

and control. While Porcaro (2011) and Onyesolu et al. (2013) acknowledge that constructivism

has many critics that do not feel it is really a learning theory, they also recognize the importance

of its impact on educational design and theory. Porcaro notes that many critics feel constructivism

ignores basic instructional science, while others feel constructivism is too broad of a concept to be

a theory and therefore should be an epistemology. Porcaro’s response is that these critics focus

mostly on what practices are not constructivist but then fail to describe what category these non-

constructivist practices fall under. Onyesolu et al. (2013) note how constructivism has been labeled

as everything from a fad to a religion, all in contrast to being a true learning theory. The response

from Onyesolu et al. (2013) also echoes one of Poracro’s points: “it cannot be over-emphasized

that a learner enters his learning situation with pre-conceived notions or ideas about many

phenomena” (p. 40).

Seeing that there are widely different aspects associated with constructivism, the question

becomes: “do all aspects of constructivism relate to power dynamics”? According to Foucault

(1980), power needs discourse in order to be effective in society. Therefore, the radical

constructivism of Ernst von Glaserfield would not be much of a part of the discussion of power

dynamics in education because in radical constructivism “communication is not necessary to

involve sharing meaning among participants” (Liu & Chen, 2010, p.64). Of course, radical

constructivism is important in understanding how some experts believe learners construct

knowledge within their mind. But eventually, in order for this construction of knowledge to be

able to affect power or regulation of learning, it will need to be communicated as discourse. For

this process, the discussion will turn to the ideas of social constructivism.

The concept of social constructivism is most often associated with Soviet psychologist Lev

Vygotsky. According to Liu and Chen (2010):

Current Issues in Education, 21(2)

6

Crosslin: Self-Mapped Learning Pathways

From Vygotsky's perspective, learners construct meaning from reality but [do] not

passively receive what [they] are taught in their learning environment. Therefore,

constructivism means that learning involves constructing, creating, inventing, and

developing one's own knowledge and meaning. The role of teacher is a facilitator

who provides information and organizes activities for learners to discover their own

learning. (p. 65)

This is not far off from von Glaserfield’s radical constructivism in some ways. Power has shifted

away from an all-powerful expert that is transferring knowledge to a learner that is responsible for

constructing knowledge. Oftentimes, the power over oneself is seen as the opposite of the

ecological or expert power that instructors typically control in classroom settings (McLeod & Lin,

2010). However, Vygotsky did not see the process of acquiring knowledge as a solo endeavor. He

proposed the idea of the zone of proximal development: an identifiable “gap” that exists between

what learners can achieve individually and what the same learners can achieve with the help of

more knowledgeable others through engagement and social interactions (Vygotsky, 1978). The

zone of proximal development is a key factor in not only the shift from teacher-centered

instructivist power to student-centered social constructivist power, but also in the shift from

learning as an individualistic activity to learning as a social activity that is shared among learners

(Watson, 2001). To link back to Foucault, the zone of proximal development is one arena where

power is produced, accumulated, and circulated as a function of discourse.

The main modern issue with the zone of proximal development is that it still depends on a

more knowledgeable other to guide learners to the point of developing their own learning

(Vygotsky, 1978). This would still closely mirror a typical formal learning situation in grade

school or college. What about online situations where there are many knowledgeable individuals

coming together to dig deeper into a topic they are already familiar with? Andersen and Ponti

(2014) notes how the zone of proximal development can be seen as operating at two levels:

individual and collective. Some have worked on newer learning frameworks to address the

growing needs of society for learning through connecting and engaging with others in less formal

situations. In these spaces, creating the scaffolding needed for the zone of proximal development

is both collective and self-regulated in nature. Additionally, scaffolding for open learning when

many learners might start the educational process but not complete it can become problematic

when the more knowledgeable others decide to not complete the learning process. The next section

will examine one prominent attempt at a new learning framework that has gained attention in

recent decades.

Connectivism as Emancipatory Knowledge

Connectivism is a new learning framework that began as a reaction to behaviorism,

cognitivism, and constructivism as understood by George Siemens and Stephen Downes. To

Siemens (2005), behaviorism is a theory focused on behavior change due to stimulus and response,

as observed through external changes rather than understanding internal processes. In contrast to

behaviorism, Siemens (2005) sees cognitivism as an internal computer processing model, with

external information (input) entering the learner to be processed and stored in the learner’s

memory. Finally, Siemens (2005) views constructivism as a process where learners actively

attempt to create and construct meaning by understanding their experiences. To sum these up,

Siemens (2005) observes that “all of these learning theories hold the notion that knowledge is an

Current Issues in Education, 21(2)

7

Crosslin: Self-Mapped Learning Pathways

objective (or a state) that is attainable (if not already innate) through either reasoning or

experiences” (p. 4).

After examining the concepts of behaviorism, cognitivism, and constructivism, Siemens

and Downes came to the conclusion that these learning theories did not address modern learning

issues adequately. Among the problems that they noted were issues such as learners changing

fields often through their lifetime, the rise of the importance of informal self-regulated learning,

the ability to off-load some cognitive tasks previously covered in older learning theories to

technology, and the rising need to know where to find knowledge. But their main issue with older

learning theories was that

A central tenet of most learning theories is that learning occurs inside a person.

Even social constructivist views, which hold that learning is a socially enacted

process, promotes the principality of the individual (and her/his physical presence

– i.e. brain-based) in learning. These theories do not address learning that occurs

outside of people (i.e. learning that is stored and manipulated by technology). They

also fail to describe how learning happens within organizations. (Siemens, 2005, p.

4)

In other words, Siemens’ concern is that, even though the power of learning can exist with an

instructor or a learner, there was little room for a shared power structure that allowed for learning

to occur socially as a group according to existing learning theories. His solution for the problem

he identified was to propose a new theory, along with Downes, called connectivism. In Siemens’

(2005) own words

Connectivism is the integration of principles explored by chaos, network, and

complexity and self-organization theories. Learning is a process that occurs within

nebulous environments of shifting core elements – not entirely under the control of

the individual. Learning (defined as actionable knowledge) can reside outside of

ourselves (within an organization or a database), is focused on connecting

specialized information sets, and the connections that enable us to learn more are

more important than our current state of knowing. (p. 6)

In many ways, this would link back to Foucault’s (1980) point about emancipatory knowledge,

that in order to be free from disciplinary power, one needs to be anti-disciplinarian (chaotic and

complexity) while also liberated from the power of the principle of sovereignty (learning as

process that is not entirely under the control of any individual). However, connectivism remains

under the concept of societal power structures that Foucault (1980) described because it involves

the “production, accumulation, circulation and functioning of a discourse” (p. 93). All of this

assuming, of course, that connectivism is a true learning theory and not just a random collection

of interesting ideas.

Some debate has occurred over whether connectivism is really a learning theory or not

(Bell, 2011; Calvani, 2009; Harasim, 2012). Calvani (2009) makes a strong point that replacement

of other theories is not necessary, because a more nuanced view should be taken: pragmatically

there is probably not one dominant learning theory that can only be used at all times. In other

words, learning is not always about behaviorism or constructivism, but behaviorism and

constructivism utilized at the appropriate times in the appropriate manner. Bell (2011) agreed with

Current Issues in Education, 21(2)

8

Crosslin: Self-Mapped Learning Pathways

Calvani that there is more than one applicable theory for all of learning. However, Bell examined

various aspects of the arguments for and against connectivism as a new learning theory and came

to an interesting conclusion. Bell sees connectivism as a phenomenon because it “has not

established itself as a distinct learning theory, although its epistemology can make a contribution

to new paradigms of learning…and its study and practice can provide a rich context for exploring

those paradigms” (Bell, 2011, p. 106). Within these contexts for exploring various paradigms is

where power dynamics most likely need to be worked out, especially since – as Bell points out –

connectivism does contain an epistemology. As previously quoted, this epistemology places

knowledge in an interesting arena that has not been explored extensively in the past: a group

artifact that is not just transferred from one person to another or occurring inside of any given

person, but one that is shared and communicated through discourse and engagement (electronic

and otherwise).

Power and Control Dynamics in Learning Design

This examination of power dynamics in learning leaves us with the conclusion that all

learning modalities contain intentional or unintentional structures of power and control. Usually

this means that one agent is in control and the other must follow the pathway that this controlling

agent prescribes. In a typical formal learning modality, this relationship is set up so that the

instructor has complete power and control over the direction, regulation, and determination of the

learning process. In other words, the instructor determines what will be learned, tells the learner

how to learn what was determined, and then creates a set of rewards and/or punishments to

motivate or force the learners to complete that pre-determined set of learning objectives. Some

less-structured courses allow learners to have some input in how they motivate themselves (for

example, online courses often rely less on instructor presence and more on learner self-regulation)

or even some input on the direction that the learning process might take. By contrast, informal

education is often a process that is completely up to the learner: the learner has the power and

control to determine what they want to learn, direct a pathway through the available resources, and

regulate their own learning to complete the process.

While some may feel that one modality or power/control structure is better than the other,

the complex reality may be that many need both at different points in the learning process for any

given topic or skill. However, most courses are designed so that all learners are subject to one

power structure (usually instructor-led, but occasionally student-centered group consensus) for the

entire duration of the course. This approach has created a dehumanizing effect on education in

general, with many people seeing education as pointless, unrealistic, and tedious. Therefore, one

of the main goals of the Self-Mapped Learning Pathways concept is to not only return control over

learning modality back to the learner, but to also humanize the learning process by recognizing

that all learners are unique and different, thus allowing them to create a customizable pathway of

personalized modalities through the course (Bali & Caines, 2018).

Customizable Modality versus Courses That Blend Modalities Together

One response to the Self-Mapped Learning Pathways concept is to point out that many

courses already have elements of both instructor and learner control. This is quite often true. Many

courses already do blend modalities into a single course pathway. The distinction between the Self-

Mapped Learning Pathways methodology and courses that blend modalities is that it actually

creates two complete modalities through the course content and activities. The instructor-led

modality is a complete course pathway that learners can choose to stick with for the entire course

Current Issues in Education, 21(2)

9

Crosslin: Self-Mapped Learning Pathways

and still be considered as having “completed” the course. Additionally, the student-centered

modality is also a complete course pathway that learners can choose to stick with for the entire

course and still be considered as having “completed” the course. The unique aspect of the Self-

Mapped Learning Pathways design is that learners can choose one pathway, both pathways, or a

custom mix of either pathways at any point in the course, changing their choice as often as they

like. A unique combination of design features and technology tools enables this customization.

Those features will be explored later in this article. However, at this point an exploration of the

history of the Self-Mapped Learning Pathways concept is in order.

History of Self-Mapped Learning Pathways

One possible way to deal with issues that power dynamics create is to allow learners to

choose which power dynamic they would like to utilize while moving through course content and

activities. The Self-Mapped Learning Pathways concept started out as an attempt to create a new

type of Massive Open Online Course (MOOC). In the Fall of 2014, several Universities (led by

the Learning Innovation and Networked Knowledge (LINK) Research Lab at the University of

Texas at Arlington) came together to offer an open course on learning analytics. Initiated by Dr.

George Siemens, the Data, Analytics, and Learning MOOC (DALMOOC) was envisioned as a

unique course design structure that was initially labeled a “dual-layer” approach. DALMOOC was

designed with two complete layers from two different design epistemologies: one that was

instructor-led (instructivism) and one that was focused on connected learning (connectivism).

Learners were granted the freedom to choose an individualized pathway through the course

involving either layer, both layers, or a custom combination of both at any given point in the

course.

The initial design for DALMOOC involved several different types of technology. The first

was a learning management system (LMS) called edX that hosted the instructor-led content,

videos, assignments, and discussion forums. The second was a competency-based system called

ProSolo that allowed learners to connect with each other to interact around shared competencies

and submit peer feedback. Additionally, learners were encouraged to create their own blogs or

social media accounts to connect and interact outside of the LMS or ProSolo. Because of the

complex nature of the course design, a visual syllabus was created to help explain the dual-layer

structure. Additionally, many technologically-adaptive software solutions such as QuickHelper

and Bazaar were integrated into edX. Several design considerations were considered (such as

Assignment Banks and scaffolding between the layers), but not implemented by course launch

time.

Over 23,330 people registered for the first DALMOOC offering, with an estimated 13,535

learners showing at least some form of activity in the course (Dawson et al., 2015). Over 1,500

learners were active up to the last week; however, it is difficult to tell how many of those completed

the entire course and how many took a “pick and choose” approach to the course content and

activities. A few studies have looked at various issues that arose in the design. Crosslin and

Dellinger (2015), when examining the social media feedback quotes on DALMOOC, noted:

At first glance, these quotes might seem to indicate that the course structure was

not well understood. However, a closer look could also reveal that each participant

forged their own path through the course in different ways, thereby validating the

dual-layer design as effective (at least, in some cases). (p. 253)

Current Issues in Education, 21(2)

10

Crosslin: Self-Mapped Learning Pathways

After examining data and interviews from DALMOOC, Crosslin, Dellinger, et al. (2018) also

concluded that course participants seemed to value the ability to choose the pathway that they

utilize to engage the course in. However, additional research is needed to improve the technical

and design aspects of the framework. Rosé et al. (2015) noted that while the dual-layer model

shows interesting results, the frustration and confusion expressed by learners indicates the need to

improve the tools that help learners connect, make decisions, and find support while navigating

the course structure. Dawson et al. (2015) also point out the idea of self-regulated learning has

been neglected in the conversation about learning pathways.

In 2015, lessons learned from DALMOOC were applied to the Winter 2015 offering of the

Humanizing Online Learning MOOC (HumanMOOC). The learner-facing side of the course

focused less on the dual-layer aspect of the design, and more on the leaners creating their own

pathway through the course options. This necessitated a shift from the term “dual layer” to

“customizable modalities” to describe the course structure (Crosslin, 2016). Greater scaffolding

was built into the course syllabus, while less tools were implemented in the overall design.

Instructure Canvas was utilized to create the instructor-led modality, while a website referred to

as the “Neutral Zone” was set up to facilitate learners creating their own custom pathway through

the course content, activities, and options. This Neutral Zone also contained the Assignment Bank,

designed to help scaffold leaners into creating their own assignment ideas by giving a “bank” of

assignment ideas they could consider outside of the one option given in the instructor-led modality

in Canvas.

Qualitative analysis into the participants experiences (Crosslin, 2016) yielded two

interesting themes: course participants did desire an overall learning experience that was tailored

to their personal learning preferences, but the technical and design limitations of the course created

barriers in their learning experiences. Based on this feedback, the concept of customizable

modalities shifted more towards the learner experience of creating their own pathway,

necessitating another terminology shift to “Self-Mapped Learning Pathways.” Currently, research

is being conducted into how traditional online History courses can adopt elements of Self-Mapped

Learning Pathways (Crosslin et al., 2019).

Conceptualizing a Self-Mapped Learning Pathways Course

The key concept in a Self-Mapped Learning Pathways course is that learners are free to

choose which modality to participate in at any given moment of the course. Learners are able to

choose either pathway, both pathways, or a custom mix of each pathway as needed. This choice

does not have to stay the same for the entire course – it can change at any moment. For example,

a learner may decide that the content in the first week of a course is a review of content they already

know. So this learner could chose to go to Twitter and connect with other advanced learners. This

group decides to look at a deeper application of the introductory topic that is more in line with

their real-life contexts. As the week goes on, the learner realizes that there are some gaps in their

knowledge of the content, so they decide to go back into the learning management system to see

what the instructor is teaching about those gaps. After gaining the missing knowledge, the learner

re-joins the spontaneous group to dig deeper into the topic. Stephen Downes’ (2017) summary of

open pedagogy is the best way to summarize this mindset: “follow my model or not; it's your

choice” (para. 1).

To best facilitate this in a course, pathway options can be anchored with a weekly start and

end point. Typically, the starting point is some sort of open or neutral space/zone that lays out the

pathway choices for the week or module. The ending point is often a competency or set of

Current Issues in Education, 21(2)

11

Crosslin: Self-Mapped Learning Pathways

competencies that focuses more on how learners demonstrate the skill or knowledge they gained

that week than on the method that they utilize to demonstrate their knowledge.

The key power dynamic in Self-Mapped Learning Pathways design is that the learner is

always in control of what modality they choose. The instructor does not dictate at what times the

learners are all watching a video, or when all learners are forming groups and interacting. Instead

of a linear pathway that is dictated for all learners at the same time, the pathway options through a

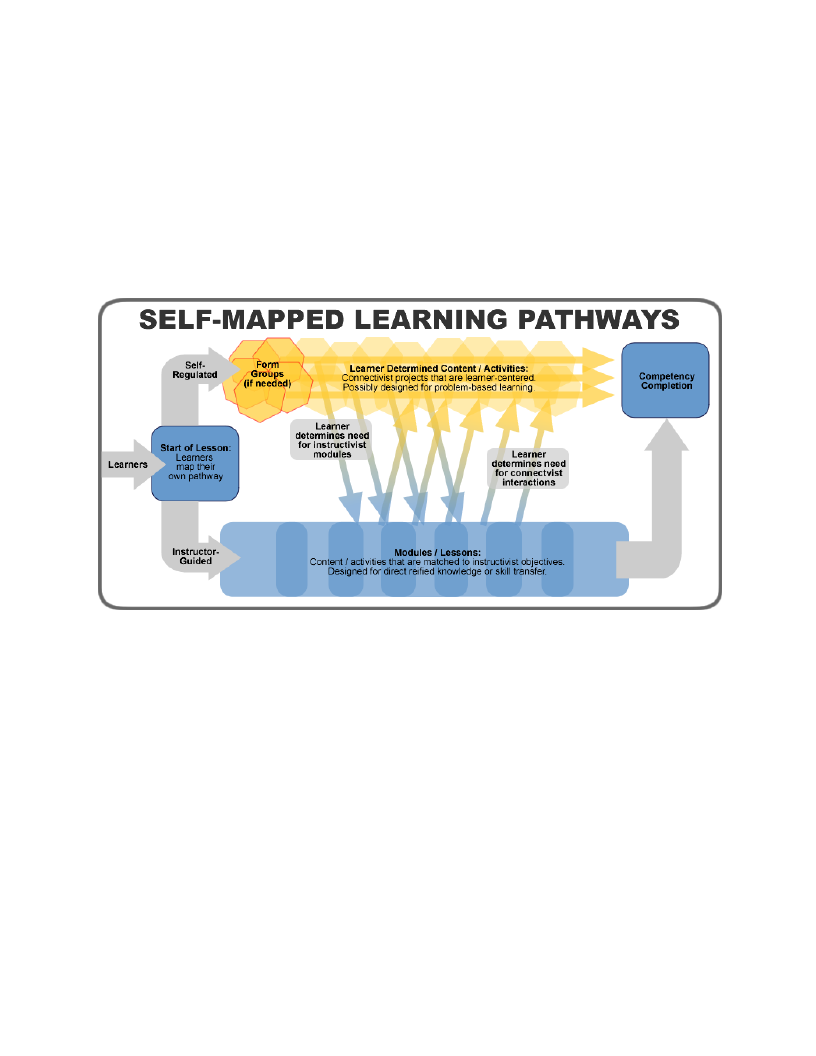

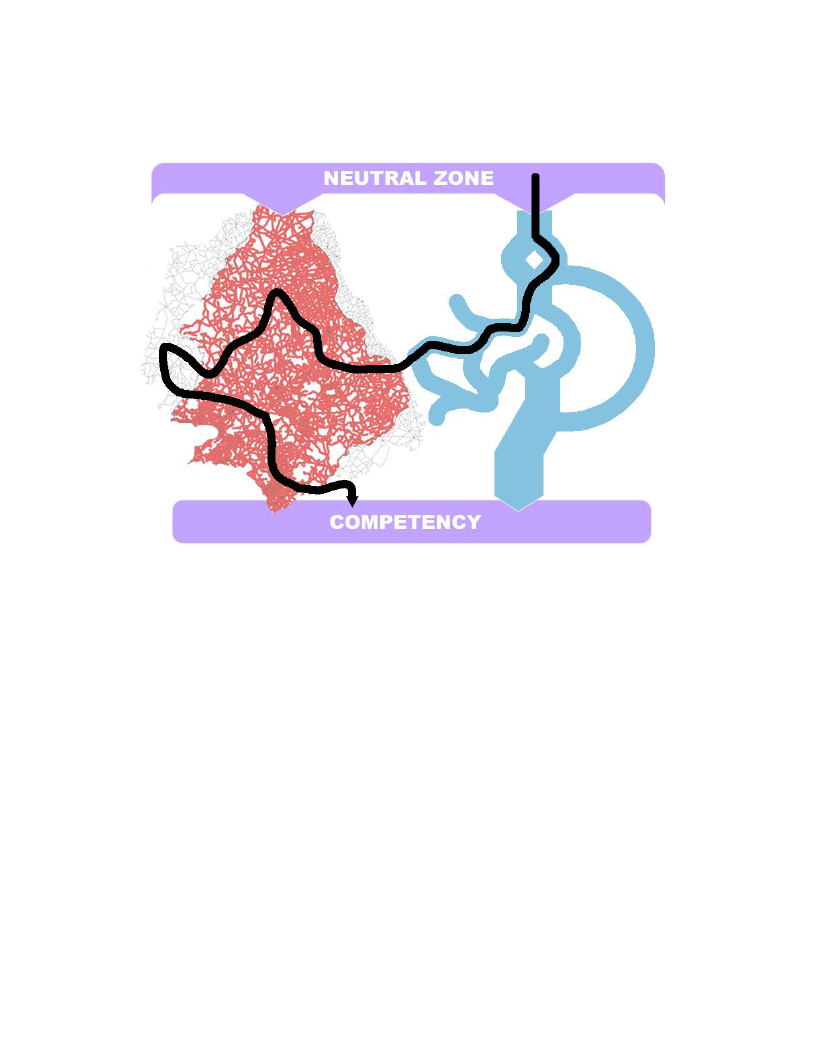

Self-Mapped Learning Pathways course will resemble something like Figure 1.

Figure 1

Diagram of Self-Mapped Learning Pathways design

In Figure 1, learners enter into a course module through an area called the Neutral Zone.

This area simply presents a brief introduction to the module, the competencies for the module, and

explanations of both modality options. The learner would then follow links to the modality that

they prefer. In the connectivist modality, they would be encouraged to utilize tools that would help

them connect with others as well as with the content they desire. For the instructivist modality,

learners would find themselves on a linear path through the content that the instructor feels would

best lead them towards competency completion. Instructors would also develop the competencies

into more formal learning objectives in this pathway. At any point learners could decide that they

need either more instructor-led content or more connection with other learners or content and

switch over to the other modality (or add it to the one they are current participating in). Learners

continue to follow, change, or mix either modality until they have completed the module’s

competencies. In open online courses, the competencies would only serve as certification points

for those seeking official statements of course completion such as grades, badges, or certificates.

In more traditional or formal courses, they would serve as evaluation points based on open-ended

rubrics or portfolio assessments.

Current Issues in Education, 21(2)

12

Crosslin: Self-Mapped Learning Pathways

While this process may seem straight forward in theory, the reality of this design is that

specific modalities through the course will not look so structured. Actual pathways as designed

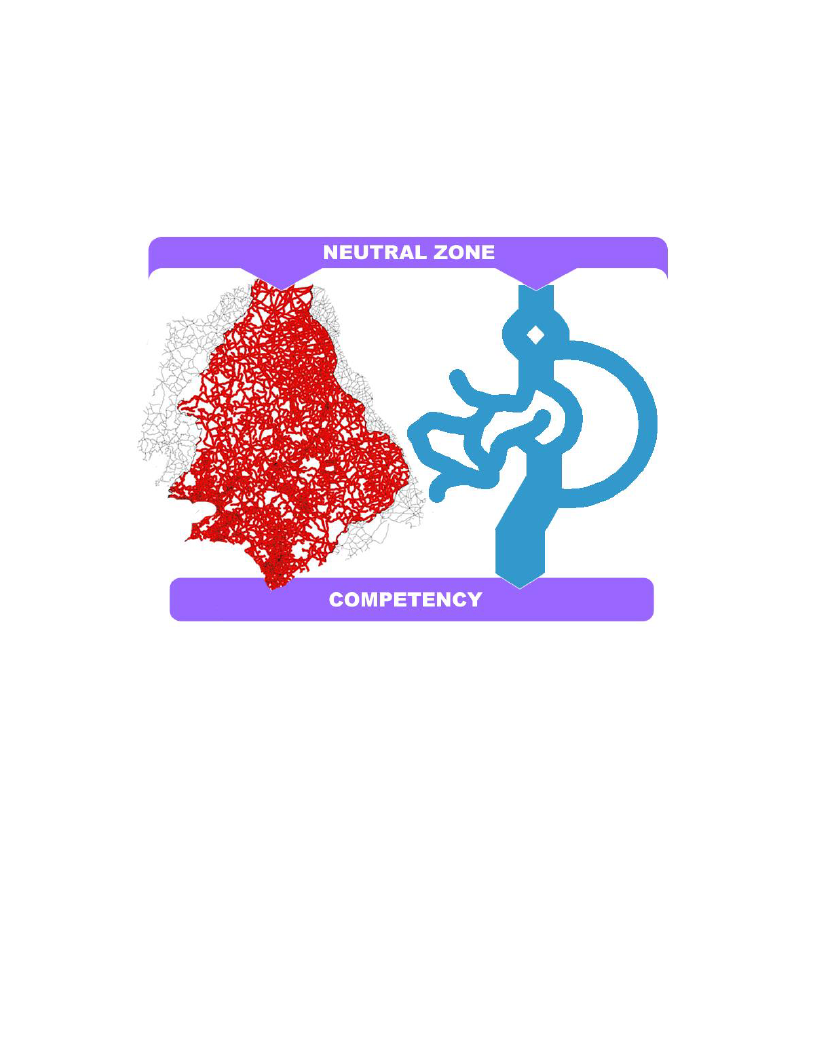

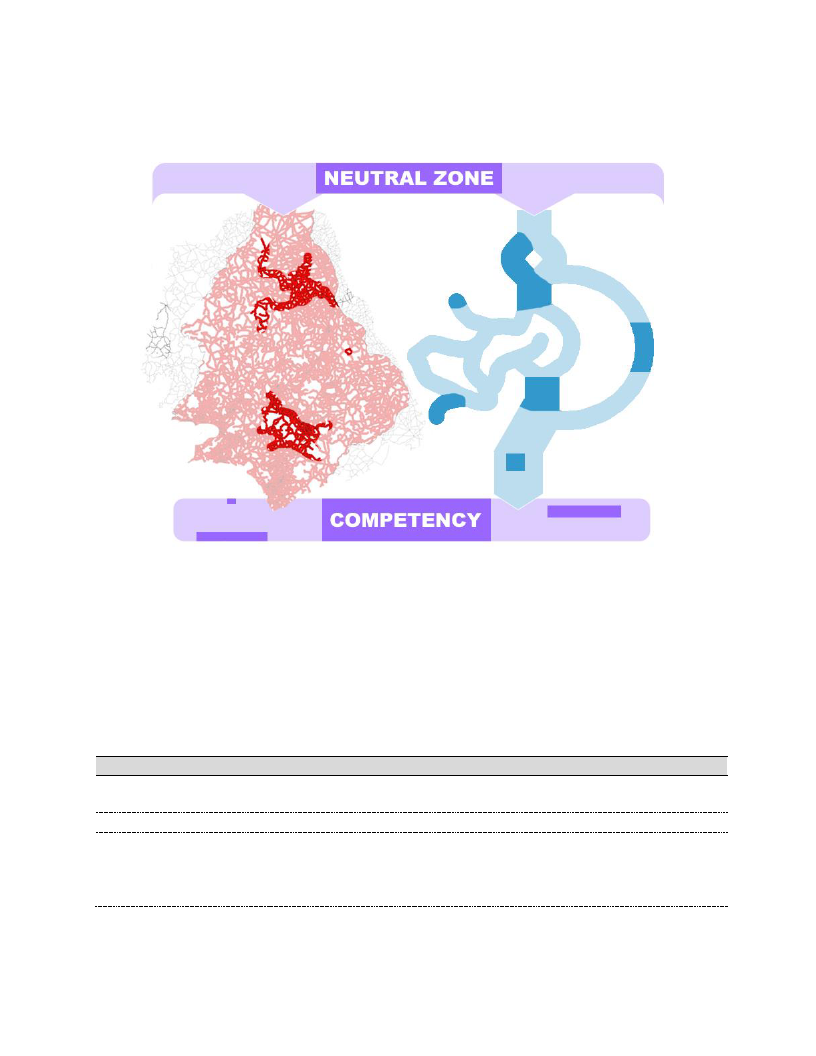

will look less linear and more like Figure 2.

Figure 2

Pathway possibilities

Figure 2 shows how the design of a Self-Mapped Learning Pathways course module will be less

structured – the blue lines represent the instructivist pathway that can have many options and even

circular design, while the red lines represent the chaotic nature of connectivism that includes many

official possibilities as well as unofficial possibilities (represented by the gray lines). This

paradigm will allow learners to self-map their own personalized pathway through the module

content and activities. For example, an actual learner’s pathway could end up looking something

like Figure 3.

Current Issues in Education, 21(2)

13

Crosslin: Self-Mapped Learning Pathways

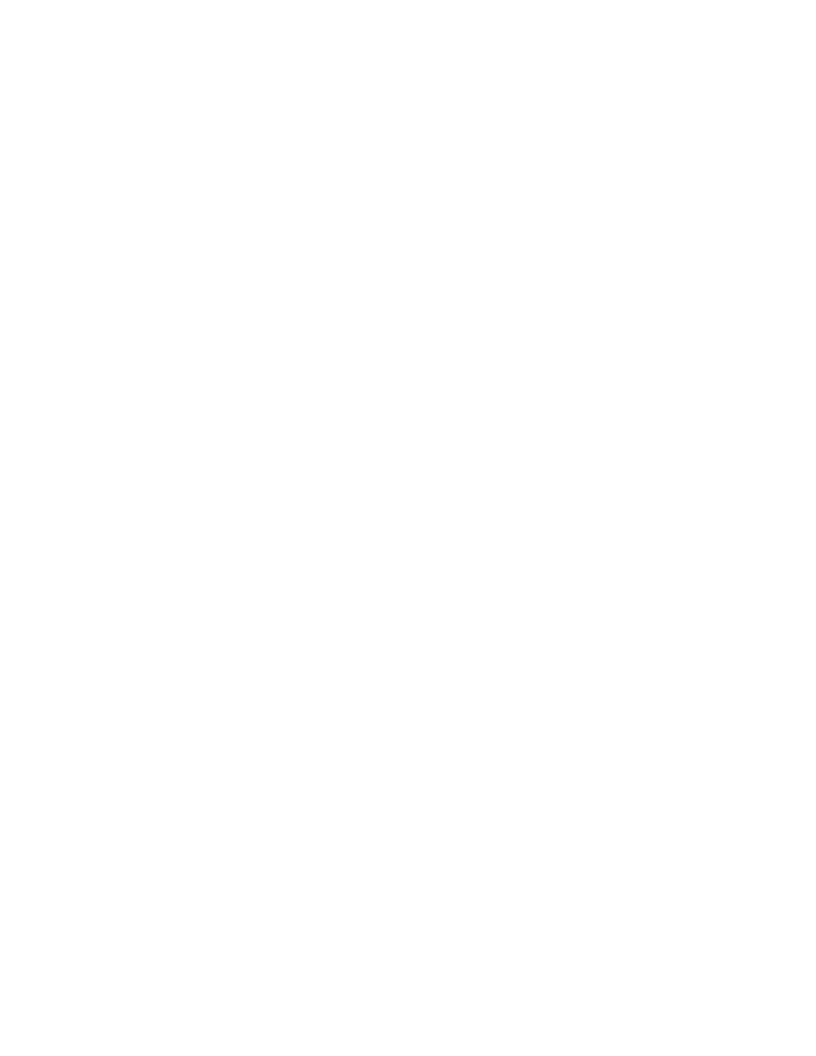

Figure 3

Self-mapped pathway example 1

Figure 3 represents how a theoretical learner could begin a course module in the blue instructivist

modality, switch over to the red connectivist modality, find content outside of the official channels

in the gray area, and then bring it all back together for competency completion. However, it is

possible that learner pathways may not even end up being linear. Learners may end up picking and

choosing parts of the course, as demonstrated in Figure 4.

Current Issues in Education, 21(2)

14

Crosslin: Self-Mapped Learning Pathways

Figure 4

Self-mapped pathway example 2

Figure 4 represents how a theoretical learner might choose different parts of the neutral zone, the

blue instructivist modality, the red connectivist modality, and the gray areas outside of the official

channels to complete the module competencies that they are interested in.

Table 1 contains a summary of the various modalities. The first column lists the various

factors such as modality and technology applied in each modality, with the rest of the table

examining how those factors were designed in the course.

Table 1

Summary of Modalities and Pathways

Factor

Modality:

One Modality

Instructor-led

Epistemology:

Technology Utilized:

Instructivism

LMS (text, video,

discussion tools,

assignment tools)

Google Hangouts

One Modality

Learner-focused

Connectivism

Twitter

Blogs

Google (plus,

Hangouts)

Two Modalities

Instructor-led mixed

with learner-focused

Connectivism

LMS

Twitter

Blogs

Google (plus, Hangouts)

Current Issues in Education, 21(2)

15

Crosslin: Self-Mapped Learning Pathways

Building a Self-Mapped Learning Pathways Course

When building a Self-Mapped Learning Pathways course, course designers will need to

keep in mind that learner choice is the adaptive mechanism in the course. Therefore, the course

will need to have different options – many of them open ended – for learners to choose from. The

designer must resist the temptation to design the choices into the course for the learner. In some

instances, this may be difficult to avoid for those that have strong bias for certain epistemological

stances such as instructivism or connectivism. As long as the designer and/or instructor is aware

of their bias, and willing to take steps to not force those biases on all learners, the course will work

more smoothly towards the goal of self-determined learning.

However, please keep in mind that not all aspects of Self-Mapped Learning Pathways have

to be added into every course. Different courses will have different requirements from accrediting

bodies, university departments, corporate oversight boards, and many other controlling interests.

Where applicable, these interests will need to be accounted for in the design. Where the course

designer has the flexibility to allow for self-determination, various aspects of Self-Mapped

Learning Pathways can be implemented into courses.

Designing the Instructivist Modality

The best place to start is with a well-designed, fully-formed instructor-guided pathway that

all learners could potentially follow from beginning to end to complete the course. This pathway

does not have to be simple or linear: it could have group work, various choices in content, problem-

based learning, etc. However, the key to this pathway is that most or all learning decisions are

made by the instructor. Remember: learners are not required to follow this pathway, but it has to

be there for those that choose to do so.

Creating an instructivist modality needs to start with a set of competencies that will guide

both the instructivist and connectivist modalities in the course. This is where the design

methodology gets a little tricky. The instructivist modality will have a more detailed set of

objectives for completing the competencies, but the connectivist modality will not. Therefore, the

competencies need to be broad enough to allow learners the flexibility to map their own pathway,

without being specific enough to start making the educational decisions for the learners. Once the

course has a good set of competencies, these can be refined into objectives that can guide the

learners when they choose the instructivist modality (see Crosslin, 2014). For the purpose of

pathways mapping, competencies would focus on behaviors (what learners are learning), leaving

the conditions (how they will learn) and criteria (how they will prove they learned what they did)

up to the learner. In the objectives in the instructivist modality, these conditions and criteria are

also defined for the learner.

Therefore, the competencies will help organize the overall course structure, while focusing

those competencies into objectives will form an instructivist modality for the learners that choose

that option. Organizing long courses into smaller sections (such as by week), each with a start and

end point, can help keep learners on track with competencies. However, flexibility in due dates is

key for those learners that might need to look ahead or go back and repeat past content in order to

make their own pathway.

Designing a well thought out instructivist course pathway is extensively covered in many

books, websites, and other resources (see Crosslin, Benham, et al., 2018, for an example).

Therefore, covering those topics is outside the scope of this paper. However, special consideration

should be given to assessing learner artifacts. Be careful to not create a rigid system of assessment

Current Issues in Education, 21(2)

16

Crosslin: Self-Mapped Learning Pathways

just yet, as the design of the connectivist modality and other course options may influence how

learners are assessed.

Making Space for the Connectivist Modality

While the connectivist modality is less structured, careful consideration must be given to

how learners are guided into the space, as well as to dealing with the problems that exist in less

structured spaces. Learners might benefit from being given suggestions for services to use for

networking or blogging. When doing so, make sure to provide links to resources that train learners

who are not familiar with those tools, as well as links that explore the possible dangers associated

with any online tool. No technology is neutral, therefore learners must be made aware of the pros

and cons of any service that is suggested. Additionally, learners should not be led to believe that

they are required to use any service or online tool, in the event that they become uncomfortable

with using that tool for any reason. The idea is to create space in the course for learners to map

their own pathway, including time given to adjust and change as needed.

Bridging the Modalities with a Neutral Space

One way to help learners map their own pathway could be to create a neutral space, where

all possibilities are explained, linked to, or provided. If the course is centered on this neutral space,

rather than an instructivist-leaning tool like a Learning Management System, learners might feel

free to create their own pathway. Additionally, scaffolding tools can be built into this neutral space

for those learners that are interested in forming their own path, but are uncertain as to how to

accomplish that. For example, an assignment bank of possible activity options could be provided

to give learners ideas for how to adjust the course pathway to their specific socio-cultural needs.

Learners could even be encouraged to add to this assignment bank (see Valenza, 2014, for an

example). The main idea is to focus learners on their options in building their own pathway, not

on any specific design epistemology or strategy.

Assessing Work Across Multiple Modalities

One of the more difficult parts of designing a Self-Mapped Learning Pathways course is

creating an assessment strategy that can span the different pathways that are created. Whether

through more open-ended rubrics, self-assessment, or portfolio building, this assessment method

will need to be focused on what the learner accomplished more than technical details like word

counts, rote memorization, or detailed rubric counts. Going back to the competencies that were

created, make sure that any form of assessment focuses on the behaviors over conditions or criteria,

in a way that can span both instructivist and connectivist modalities. One possibility for this is to

look at the pathway that learners self-map as a portfolio of what they learned.

Learning Pathways Mapping

The biggest challenge for learners when mapping learning pathways is that technology to

accomplish the actual mapping does not yet exist. However, a combination of tools can be used to

help learners with the process. The basic process is to have learners create a map of the pathway

they would like to take through the course, follow the map and change it as needed throughout the

course, and then reflect on the process at the end. Any tool could be used to accomplish this, such

as word processing tools, blogging tools, or even a notepad. One possibility is to use a story making

tool like Wakelet to create the map; then have learners follow the map and create artifacts on

Current Issues in Education, 21(2)

17

Crosslin: Self-Mapped Learning Pathways

services like WordPress, Twitter, YouTube, etc; and finally have learners reflect on the pathway

in an annotation tool like Hypothes.is. For an example of this process, see Crosslin (2017).

Conclusion

This article does not serve as an exhaustive list of every design and theoretical issue related

to Self-Mapped Learning Pathways. Research and writing on this emerging mindset are ongoing.

As new findings, blog posts, and ideas are created, they will be cataloged at the author’s website

(Crosslin, 2019). A special note should be made that the particular methods mentioned in this

article are not the only way to approach pathways mapping. Others have looked at mixing different

epistemologies other than instructivism and connectivesm (Kilgore & Al-Freih, 2017). However,

the main goal always remains the same: to allow learners to take control and ownership over their

learning pathways, bringing about a realization of heutagogical student-centered learning that

many in education desire to obtain.

References

Ally, M. (2004). Foundations of educational theory for online learning. Theory and Practice of

Online Learning, 2, 15-44.

Anders, A. (2015). Theories and applications of massive online open courses (MOOCs): The

case for hybrid design. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed

Learning, 16(6), 39-61.

Andersen, R., & Ponti, M. (2014). Participatory pedagogy in an open educational course:

Challenges and opportunities. Distance Education, 35(2), 234–249.

Bain, J. D. (2003). Slowing the pendulum: Should we preserve some aspects of instructivism? In

EdMedia+ Innovate Learning (pp. 1382-1388). Association for the Advancement of

Computing in Education (AACE).

Bali, M., & Caines, A. (2018). A call for promoting ownership, equity, and agency in faculty

development via connected learning. International Journal of Educational Technology in

Higher Education, 15(46).

Basham, J. D., Hall, T. E., Carter Jr, R. A., & Stahl, W. M. (2016). An operationalized

understanding of personalized learning. Journal of Special Education Technology, 31(3),

126-136.

Bell, F. (2011). Connectivism: Its place in theory-informed research and innovation in

technology-enabled learning. The International Review of Research in Open and

Distance Learning, 12(3), 98-118.

Blaschke, L. M. (2012). Heutagogy and lifelong learning: A review of heutagogical practice and

self-determined learning. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed

Learning, 13(1), 56-71.

Calvani, A. (2009). Connectivism: new paradigm or fascinating pot-pourri? Journal of E-

learning and Knowledge Society, 4(1).

Clark, R. E. (1983). Reconsidering research on learning from media. Review of Educational

Research, 53(4), 445-459.

Crosslin, M. (2014, July 7). Bridging learners from instructivism to connectivism [Web log

entry]. Retrieved from: http://www.edugeekjournal.com/2014/07/11/bridging-learners-

from-instructivism-to-connectivism/

Current Issues in Education, 21(2)

18

Crosslin: Self-Mapped Learning Pathways

Crosslin, M. (2016). Customizable modality pathway learning design: Exploring personalized

learning choices through a lens of self-regulated learning (Doctoral dissertation).

Retrieved from University of North Texas Libraries, Digital Library.

(digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc849703/m1/1/)

Crosslin, M. (2017, March 28). Creating a self-mapped learning pathway [Blog Post]. Retrieved

from https://www.edugeekjournal.com/2017/03/28/creating-a-self-mapped-learning-

pathway/

Crosslin, M. (2019). Self-mapped learning pathways: Research, reviews, and posts about self-

mapped learning pathways [website]. https://mattcrosslin.com/pathways/.

Crosslin, M., Benham, B., Dellinger, J. T., Patterson, A., Semingson, P., Spann, C., Usman, B.,

& Watkins, H. (2018). Creating online learning experiences: A brief guide to online

courses, from small and private to massive and open. Mavs Open Press.

Crosslin, M. & Dellinger, J. T. (2015). Lessons learned while designing and implementing a

multiple pathways xMOOC + cMOOC. In D. Slykhuis & G. Marks (Eds.), Proceedings

of Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference

2015 (pp. 250-255). Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education

(AACE).

Crosslin, M., Dellinger, J. T., Joksimović, S. & Kovanović, V. (2018). Customizable modalities

for individualized learning: Examining patterns of engagement in dual-layer MOOCs.

Online Learning Journal, 22(1), 19-38.

Crosslin, M., Dellinger, J. T., Milikic, N., Jovic, I., & Breuer, K. (2019, March). Determining

learning pathway choices utilizing process mining analysis on click stream data in a

traditional college course. Poster session presented at the 9th International Conference

on Learning Analytics and Knowledge, Tempe, AZ.

Dawson, S., Joksimović, S., Kovanović, V., Gašević, D., & Siemens, G. (2015). Recognising

learner autonomy: Lessons and reflections from a joint x/c MOOC. In Proceedings of

Higher Education Research and Development Society of Australasia 2015.

de Kock, L. (1992). New nation writers conference in South Africa. Ariel: A Review of

International English Literature, 23(3), 29-47

Dicheva, D., Dichev, C., Agre, G., & Angelova, G. (2015). Gamification in education: A

systematic mapping study. Educational Technology & Society, 18(3), 75-88.

Dosunmu, S. A. (2013). Knowledge, ideology and the sociocultural theory of education.

Research Journal in Organizational Psychology & Educational Studies, 2(1), 12-17.

Downes, S. (2017, April 28). Perspectives on open pedagogy [Web log entry]. Retrieved from

http://www.downes.ca/post/66661

Foucault, M. (1980). Power/knowledge: selected interviews and other writings. Pantheon.

Habermas, J. (1971). Knowledge and human interests. Beacon Press.

Hase, S., & Kenyon, C. (2007). Heutagogy: A child of complexity theory. Complicity: An

International Journal of Complexity and Education, 4(1).

Harasim, L. (2012). Learning theory and online technologies. Routledge.

Kilgore, W., & Al-Freih, M. (2017). MOOCs as an innovative pedagogical design laboratory.

International Journal on Innovations in Online Education, 1(1).

Kop, R., Fournier, H., & Mak, J. S. F. (2011). A pedagogy of abundance or a pedagogy to

support human beings? Participant support on massive open online courses. The

International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 12(7), 74-93.

Liu, C. C., & Chen, I. J. (2010). Evolution of constructivism. Contemporary Issues in Education

Current Issues in Education, 21(2)

19

Crosslin: Self-Mapped Learning Pathways

Research (CIER), 3(4), 63-66.

Livingstone, S., & Brake, D. R. (2010). On the rapid rise of social networking sites: New

findings and policy implications. Children & Society, 24(1), 75-83.

Luna, J. (2016). Metamodernism. Retrieved from https://www.booksie.com/488392-

metamodernism-prolog

McLeod, J., & Lin, L. (2010). A child’s power in game-play. Computers & Education, 54(2),

517-527.

Neo, M., & Neo, T. (2009). Engaging students in multimedia-mediated constructivist learning -

students' perceptions. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 12(2), 254-266.

Onyesolu, M. O., Nwasor, V. C., Ositanwosu, O. E., & Iwegbuna, O. N. (2013). Pedagogy:

Instructivism to socio-constructivism through virtual reality. International Journal of

Advanced Computer Sciences and Applications, 4(9), 40-47.

Porcaro, D. (2011). Applying constructivism in instructivist learning cultures. Multicultural

Education & Technology Journal, 5(1), 39. http://doi.org/10.1108/17504971111121919

Rosé, C. P., Ferschke, O., Tomar, G., Yang, D., Howley, I., Aleven, V., Siemens, G., Crosslin,

M., Gasevic, D., & Baker, R. (2015). Challenges and opportunities of dual-layer

MOOCs: Reflections from an edX deployment study. Proceedings of the 11th

International Conference on Computer Supported Collaborative Learning.

Rovai, A. P., & Downey, J. R. (2010). Why some distance education programs fail while others

succeed in a global environment. The Internet and Higher Education, 13(3), 141-147.

Ruey, S. (2010). A case study of constructivist instructional strategies for adult online learning.

British Journal of Educational Technology, 41(5), 706-720.

Salen, K., Tekinbaş, K. S., & Zimmerman, E. (2004). Rules of play: Game design fundamentals.

MIT Press.

Siemens, G. (2005). Connectivism: A learning theory for the digital age. International Journal of

Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 2(1), 3-10.

Spivak, G. C. (1988). Can the subaltern speak? In R. Morris, Can the subaltern speak?

Reflections on the history of an idea (pp. 21-78). Columbia University Press.

Valenza, J. (2014, April 21). ds106 Assignment Bank [Blog Post]. Retrieved from

http://blogs.slj.com/neverendingsearch/2014/04/21/alan-levines-ds106-assignment-bank/

Vermeulen, T., & Van Den Akker, R. (2010). Notes on metamodernism. Journal of Aesthetics &

Culture, 2(1), 5677.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society. The development of higher psychological processes.

Harvard University Press.

Warren, S. J., & Wakefield, J. S. (2012). Learning and teaching as communicative actions: social

media as educational tool. In K. Seo (Ed.), Using social media effectively in the

classroom: Blogs, wikis, Twitter, and more (pp. 98-113). Francis & Taylor.

Watson, J. (2001). Social constructivism in the classroom. Support for Learning, 16(3), 140-147.

http://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9604.00206

Yukl, G. (2006). Leadership in organizations (6th ed.). Pearson.

Current Issues in Education, 21(2)

20

Crosslin: Self-Mapped Learning Pathways

Author Notes

Matt Crosslin, PhD

Orbis Education, Instructional Designer II; University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, Part-Time

Faculty

matt@mattcrosslin.com

Guest Editor Notes

Sean M. Leahy, PhD

Arizona State University, Director of Technology Initiatives

sean.m.leahy@asu.edu

Samantha Adams Becker

Arizona State University, Executive Director, Creative & Communications, University

Technology Office; Community Director, ShapingEDU

sam.becker@asu.edu

Ben Scragg, MA, MBA

Arizona State University, Director of Design Initiatives

bscragg@asu.edu

Kim Flintoff

Peter Carnley ACS, TIDES Coordinator

kflintoff@pcacs.wa.edu.au

Current Issues in Education, 21(2)

21

Crosslin: Self-Mapped Learning Pathways

Volume 22, Issue 1

January 7, 2021

ISSN 1099-839X

Readers are free to copy, display, and distribute this article, as long as the work is attributed to the

author(s) and Current Issues in Education (CIE), it is distributed for non-commercial purposes only, and no alteration

or transformation is made in the work. More details of this Creative Commons license are available at

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/. All other uses must be approved by the author(s) or CIE. Requests

to reprint CIE articles in other journals should be addressed to the author. Reprints should credit CIE as the original

publisher and include the URL of the CIE publication. CIE is published by the Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College at

Arizona State University.

Editorial Team

Consulting Editor

Neelakshi Tewari

Lead Editor

Marina Basu

Section Editors

L&I – Renee Bhatti-Klug

LLT – Anani Vasquez

EPE – Ivonne Lujano Vilchis

Review Board

Blair Stamper

Melissa Warr

Monica Kessel

Helene Shapiro

Sarah Salinas

Faculty Advisors

Josephine Marsh

Leigh Wolf

Current Issues in Education, 21(2)

22