Volume 22, Issue 1

January 7, 2021

ISSN 1099-839X

Shaping the Futures of Learning in the Digital Age

Thinking Backward: A Knowledge Network for the Next Century

Tom Haymes

Ideaspaces.net

Abstract: The standards of educational information exchange are still firmly rooted in a

Newtonian paradigm that emphasizes strict rules of information exchange. With the explosion of

information since World War II, and especially its accessibility through the mechanism of the

internet, this paradigm has become a barrier to effective exchanges of information at all levels.

Vannevar Bush recognized this problem as early as 1945 and provided a roadmap to addressing

it in his famous As We May Think. Douglas Engelbart and Theodore Holmes Nelson applied

Bush’s vision to technology but we have never fully realized its potential in part due to our

Newtonian information paradigm. This article argues that what Bush, Engelbart, and Nelson

proposed is essentially an Einsteinian (relativistic) notion of information flows with tools

specifically designed to facilitate the augmentation of human knowledge. It further posits what

such a system of knowledge exchange might look like and how we might begin to build it.

Keywords: Knowledge Networks, Information Exchange, Technology Systems, Paradigm Shift,

Systems of Information, Vannevar Bush, Douglas Engelbart, Ted Nelson, Concept Mapping,

Visual Thinking, Data Visualization, Textual Thinking, Networked Improvement Communities,

Dynamic Knowledge Repositories

Citation: Haymes, T. (2021). Thinking backward: A knowledge network for the next century.

Current Issues in Education, 21(2). Retrieved from

http://cie.asu.edu/ojs/index.php/cieatasu/article/view/1913 This submission is part of a special

issue, Shaping the Futures of Learning in the Digital Age, guest-edited by Sean Leahy, Samantha

Becker, Ben Scragg, and Kim Flintoff.

Accepted: 12/14/2020

Current Issues in Education, 22(1)

1

Haymes: Thinking Backward: A Knowledge Network for the Next Century

Introduction: Stepping Through Paradigms

The world of education creates, shares, and processes information according to

established sets of rules. This is necessary or we would have informational chaos. However, the

underlying paradigm of technology has shifted even as education attempts to hold onto familiar

patterns developed in a world where Newtonian physics was seen as the highest calling. In

physics, this paradigm was disrupted over a century ago by Einstein’s Theory of Relativity but

our informational paradigms have been much slower to change. The Newtonian worldview was

straightforward with rigid sets of rules and structures and this fit well within the Industrial

system of thinking that required a high degree of human coordination and conformity.

Conversely, the relativistic world is malleable with unexpected bends and gravity holes. This

kind of thinking undermines rigid patterns of thought and information exchange because rules

are conditional on circumstance. Arguably, this is a closer parallel to how humans, and groups of

humans, think. However, our knowledge systems have not kept up with physics.

As early as 1945, just as he completed the Manhattan Project, the great relativistic

endeavor of the 20th century, Vannevar Bush recognized that we were living in a relativistic

information environment but still trying to cope with Newtonian tools of thought. Douglas

Engelbart and Ted Nelson, working in subsequent decades, envisioned that the general purpose,

networked computer, with its ability to infinitely connect and recombine information, would

provide a key bridge over the discontinuity described by Bush. However, more than a century

after Einstein, most of our knowledge systems continue to be based on a Newtonian paradigm

even as our supposedly fixed points of information become ever more relativistic.

Einstein’s theories took over a decade to be accepted. Information paradigms are even

more resistant to change because we cannot experimentally confirm the disruption of the old

paradigm in the way that Arthur Eddington observationally confirmed relativity in 1919. We still

think of the computer as an electronic version of stacks of paper. This is in part due to the

desktop metaphors that Xerox implemented in the 1970s that was extended to the concept of web

“pages” by Tim Berners-Lee’s version of the World Wide Web promulgated in the 1990s. As

Nelson (2009) lamented, “A document can only exist of what can be printed” (p. 128). Despite

the limitations of this metaphor, it is unlikely that the vast majority of computer users who

flocked to the new technology in the 1980s, 1990s, and beyond would have been able to process

the kind of metaphor that Ted Nelson had in mind as he was contemplating Xanadu and

Thinkertoys in the 1970s.

The paper metaphor was a necessary bridge to introduce computing into the existing

knowledge paradigm. In doing so, however, these metaphors accelerated the information

processing ability of society without augmenting its knowledge-processing ability. It is like the

idea of a paperless office that was the rage in the early 1990s. People were surprised that

precisely the opposite happened when we essentially gave every worker access to a printing

press. The computers and networks of the 1990s and 2000s have made us tremendously efficient

in handling information but have not significantly improved our ability to turn information into

knowledge.

Like Bush, Ted Nelson and Doug Engelbart were always more focused on the

knowledge-creation aspect of computing than they were on its information storage capabilities.

They took those for granted. Instead, they were struggling with a new language designed to push

us beyond linear, textual Newtonian thinking. In the process they left behind tantalizing tools,

from hyperlinks to graphical user interfaces to the concept of the internet itself, for bootstrapping

(to use Engelbart’s term) ourselves into new ways of thinking about the world. The tools have

Current Issues in Education, 22(1)

2

Haymes: Thinking Backward: A Knowledge Network for the Next Century

been eagerly adopted and adapted to the achieve efficiencies in the existing linear paradigm but

their true potential has remained elusive.

From the 1500s to the 1800s humanity underwent a profound transformation from

magical thinking to linear scientific thinking to explain the world. Magical thinking is something

that every teacher struggles against even today as he or she tries to teach what we now call

mental disciplines such as critical thinking and the Scientific Method. As rational modes of

thinking are increasingly challenged by the relativistic information environment we find

ourselves in, this struggle can become even more intense.

Most of what we are trying to teach in our undergraduate classrooms today can be dated

back to nineteenth century concepts. There is an objective reality, at least in the sciences, and

even areas where objective reality is harder to achieve such as the social sciences and

humanities, there are tools and structures that guide us toward understanding. Until you get to the

outer edges of science and math, this is still fundamentally true. However, the outer edges of that

paradigm have resided, at least since Einstein, in a far more ambiguous structure. As Leonard

Shlain (1991) argued in Art & Physics:

Aristotle, Bacon, Descartes, Locke, Newton, and Kant all bested their respective

philosophical citadels upon the assumption that regardless of where you, the

observer, were positioned, and regardless of how fast you were moving, the world

outside you was not affected by you. Einstein’s formulas changed this notion of

“objective” external reality. If space and time were relative, then within this

malleable grid the objective world assumed a certain plasticity, too. (p. 136,

emphasis in original)

Now if you imagine a grid of information instead of a grid of space-time, the fixity of

rationalistic indexing systems of knowledge is similarly impacted by relativistic forces.

Arguably, this is what we are experiencing today. There is so much information flooding our

systems that many conceivable stories can be shaped out of cherry-picking information without

context. This is making a mockery out of rationalistic methods and structures of organizing

knowledge. Pre-rational theories such as the Flat Earth Theory and others are actually

experiencing a resurgence due to the blindness created by a lack of information perspective.

Information literacy is a constant challenge in this environment.

We need better technology to lead us out of the swamp lest we sink into it. Rationalism

increasingly finds it difficult to be a candle in the dark as Carl Sagan so eloquently put it in his

1997 book The Demon-Haunted World. Our brains struggle with rational thought and regress

easily into magical thought. As we have done for hundreds of millennia, we need to develop

technological solutions that will allow our species to survive and these need to start with

information if we hope to be able to develop answers to the next set of human challenges on the

horizon. Our most urgent need now lies in creating a technological solution that will lead us to a

paradigmatic shift in how we structure knowledge, thought, learning, and inquiry.

Vannevar Bush’s Challenge

In prescientific times people or buildings being struck by lightning were seen as the

actions of a vengeful God even if there was no logic behind those actions. Now tragedies such as

children with autism are explained as the actions of vengeful scientists even when no rationale

for such actions exist. Science is dismissed for what it doesn’t know instead of appreciated for

what it reasonably knows. The unknown and opaque is most easily explained by magic and we

Current Issues in Education, 22(1)

3

Haymes: Thinking Backward: A Knowledge Network for the Next Century

easily fall back into magical thinking patterns when we can’t seem to find a rational one. Even

what science does know is obscured by the vastness of the information it now possesses. This

was already apparent at the height of the rationalist paradigm when Vannevar Bush wrote “As

We May Think” in 1945.

Bush’s challenge to us in 1945 was directed, not at technology, but at the limitations of

human intellect and our societal capacity to manage knowledge. His technological solution, the

“Memex” was designed (but never built) with the fundamental purpose of using machines to help

us organize and, most importantly, connect our collective knowledge. He laments,

“Professionally our methods of transmitting and reviewing the results of research are generations

old and by now are totally inadequate for their purpose” (Waldrip-Fruin & Montfort, 2003, p.

37).

In the intervening 75 years nothing much has changed other than the speed and volume of

information we are dealing with. Academia is still largely stuck in an analog paradigm.

Information is still, often artificially, siloed. Instead of using digital technology to create systems

of knowledge that are associative and re-combinatorial, we have used it to create new and better

walls. Instead of organizing knowledge and creating new pathways to solving our ongoing and

persistent open-ended problems (to Bush’s worry about the Atomic Age, we can add climate

change, education, the maintenance of democracy, and dealing with the speed of technological

change), we have created a bewildering array of seemingly disconnected data that is easily

challenged and undermined. Instead of taking advantage of technology to broaden our horizons

we have doubled down on existing cultures of specialization. In short, we have created highways

when we should have been creating webs.

Douglas Engelbart, Ted Nelson, and many others iterated on Bush’s basic idea of

connecting knowledge and used that as the basis for attempting to shape technology in the

intervening decades. Yet the interconnectedness that was at the core of the visions that brought

us humanized interfaces with our technology and even the internet itself has provided a constant

source of disappointment to these thinkers. This is because true “Networked Improvement

Communities,” as Engelbart put it late in his career, have always proven to be tantalizingly out of

reach. At its core both thinkers are trying to explore a new language that fundamentally

challenges the text-based linear Newtonian thinking that is deeply ingrained in our academic

institutions and beyond. We have been willing to grasp the “shiny toys,” from hypertext to

graphical user interfaces, that their thinking has led us to. However, we have failed to understand

the deeper implications of the paradigmatic shift in thinking that they were trying to show us. We

continue to struggle with the misshapen technologies that have descended from that time.

The realities of our information environment are increasingly disconnected from our

understandings of how to address them. This is because we are in the midst of a profound shift in

the volume and intensity of information available to us and lack the necessary tools to manage

them effectively. Most fail to perceive this is the root of many of our problems or the depths to

which this will shake the foundations of our societies in education and beyond. It’s easy to look

back and analyze how previous paradigm shifts, such as the invention of the printing press in

1453, have impacted the shape of the world. However, it is unlikely that someone living in

Weimar in 1520 would have perceived the tectonic shifts that this sudden proliferation of

pamphlets would wreak upon their society or the terrible bloodshed that would mark the next

150 years. The religious wars of the 16th and 17th centuries, sparked by the paradigmatic shift

brought upon Europe by sudden democratization of information away from the Catholic Church,

are something that would be globally catastrophic today. Even in 1945 Bush saw the danger.

Current Issues in Education, 22(1)

4

Haymes: Thinking Backward: A Knowledge Network for the Next Century

The applications of science have built man a well-supplied house, and are

teaching him to live healthily therein. They have enabled him to throw masses of

people against one another with cruel weapons. They may yet allow him truly to

encompass the great record and to grow in the wisdom of race experience. He

may perish in conflict before he learns to wield that record for his true good. Yet,

in the application of science to the needs and desires it would seem to be a

singularly unfortunate stage at which to terminate the process or to lose hope as to

the outcome. (Waldrip-Fruin & Montfort, 2003, p. 47)

As Bush foresaw, information is both the source of the paradigmatic shift before us and

our only hope for surviving it. This can easily evolve into a meta-meta discussion about the

importance of designing webs of knowledge in order to understand webs of knowledge but that

is precisely where we are today. Despite the warnings of Bush, we are still woefully deficient in

our ability to leverage technology to connect diverse strands of knowledge. This results in a

fundamental lack of perspective in understanding and addressing the complex problem sets that

we need to address, whether that is designing educational systems more attuned to the nature of

societal and economic realities that face our graduates or to create open-ended efforts to address

the realities of climate change. We live in a society rich in information and poor in the

connective tissue necessary to contextualize it.

Unlike Bush in 1945, we now have the means to design systems to help us see the world

in new, relativistic ways. A thinker in 1520 might have perceived the future with the kind of

information tools we have today. However, even then he would not have been able to map an

alternative course without the power to contextualize that information. We have at our disposal a

set of tools unimaginable to this Renaissance thinker. These tools have the power to provide us

with new contexts that change the way we see. As Bush points out, “The abacus, with its beads

strung on parallel wires, led the Arabs to positional numeration and the concept of zero many

centuries before the rest of the world; and it was a useful tool—so useful that it still exists.”

(Waldrip-Fruin & Montfort, 2003, p. 42). In other words, the creation of a practical technology

led to an unexpected conceptual breakthrough.

Unlike the Renaissance thinker, in conceiving the Memex, Bush mapped out a conceptual

framework but didn’t have the capacity to realize it. Bush lamented that the technologies that he

envisioned for the Memex were still tantalizingly out of reach. The potential for creating an

abacus-like technology that would lead to unexpected outcomes is much more possible today,

however. We can, if we wish to, finally realize the vision of the Memex and open up unexpected

opportunities in seeing the world in different ways. We have the abacus but are just using it to

add numbers together instead of changing numerology. After Bush, Engelbart and Nelson sought

to couple systems that would augment thinking to tangible technology in order to address

complex problem sets. While they invented radical new ways to apply technology to human

problems, they never really undermined the paradigm they sought to subvert.

Subverting Index-Based Thinking

Our thinking systems have never evolved beyond the indexing systems pioneered in

libraries and, already in 1945, only 70 years after the first promulgations of the Dewey Decimal

System, Bush realized how counter these systems were to the way that our brains worked. He

intuitively recognized that, like many other products of the industrial age, these kinds of indexing

systems fundamentally forced humans to adapt to the machines, in this case card indexing

Current Issues in Education, 22(1)

5

Haymes: Thinking Backward: A Knowledge Network for the Next Century

systems, rather than the other way around. They force us into linear thinking processes that are

inefficient at best and misleading at worst, as well as being subject to institutional biases. His

vision for a Memex addressed this discontinuity.

Our ineptitude in getting at the record is largely caused by the artificiality of

systems of indexing. When data of any sort are placed in storage, they are filed

alphabetically or numerically, and information is found (when it is) by tracing it

down from subclass to subclass. It can be in only one place, unless duplicates are

used; one has to have rules as to which path will locate it, and the rules are

cumbersome…. The human mind does not work this way. It operates by

association. With one item in its grasp, it snaps instantly to the next that is

suggested by the association of thoughts in accordance with some intricate web of

trails carried by the cells of the brain. (Waldrip-Fruin & Montfort, 2003, p. 44)

One of the central challenges lies in our technological ability to dynamically perceive and

reshuffle patterns of information, a particularly hard task in a world constrained by paper. It

parallels the struggles that science has had to overcome when the dynamic properties of

Einstein’s relativistic world come into contact with the much more rigid rule structures of

Newton’s. The challenge that relativity posed to Newton’s universe is that it discards much of

the “indexing” system that served as the foundation for mechanistic physics. The basis for

physics could no longer be perceived as a fixed fundament. Instead, it was system of underlying

and varying relationships that could have had unexpected effects on the structured physical

world that Newton has laid out in his masterpiece Principia. It doesn’t invalidate the notions of

Newtonian physics but adds a new layer on top of it. Post-rational doesn’t have to reject

rationalism, in other words. However, it does highlight the importance of looking beyond the

fixed points of information and rigid parameters that exist in Newtonian mechanics. In a

relativistic world it’s the relationships that matter much more than the nodes that they connect.

Bush perceived this problem and set his Memex the task of solving it. However, the

vision presented in “As We May Think” tells us what the system should do but doesn’t

effectively explain how it is accomplished. For instance, how exactly do you share “trails” of

knowledge? His system of what amounts to annotation can have tremendous value, but it only

goes part of the way in creating new opportunities to view a dynamic grid of knowledge in both

space and time.

Seventeen years later Douglas Engelbart proposed a different approach to the problem in

“Augmenting Human Intellect.” In his proposal for a “A Research Center for Augmenting

Human Intellect,” Engelbart imagines an electronic version of the paper-based card indexing

system he had constructed to more dynamically manage his information network. With an

electronic system Engelbart envisioned that this could assume a far more dynamic environment

in which the information can exist.

These statements were scattered back through the serial list of statements that you

had assembled, and Joe showed you how you could either brighten or underline

them to make them stand out to your eye—just by requesting the computer to do

this for all direct antecedents of the designated statement. He told you, though,

that you soon get so you aren't very much interested in seeing the serial listing of

all of the statements, and he made another request of the computer (via the keyset)

Current Issues in Education, 22(1)

6

Haymes: Thinking Backward: A Knowledge Network for the Next Century

that eliminated all the prior statements, except the direct antecedents, from the

screen. The subject statement went to the bottom of the frame, and the antecedent

statements were neatly listed above it. (Waldrip-Fruin & Montfort, 2003, p. 105)

By deprecating the “serial” record, Engelbart is pointing out the fundamental inadequacy

of text (and paper) in his analysis of how to “augment human intellect” and his next act as a way

to struggle out of this box (with 1962 technology, I might add), is most revealing. As a way of

both explaining how his program will work as well as a goal for the program to more clearly

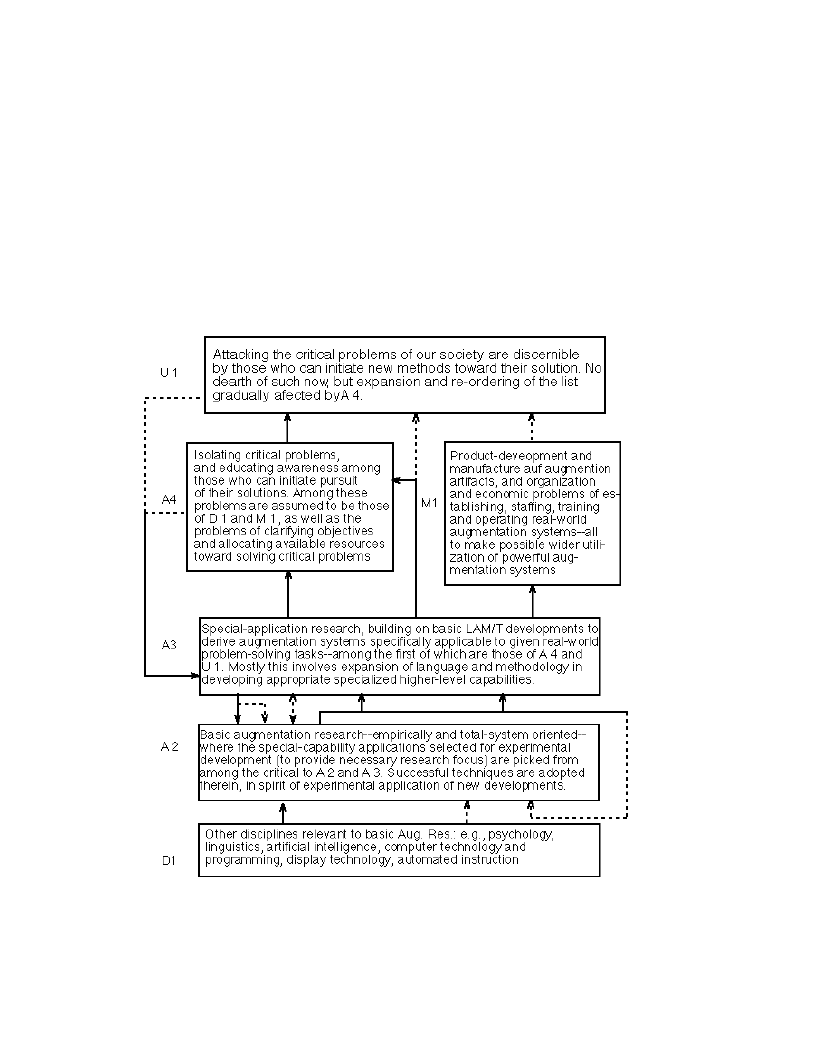

realize, he gives us this diagram.

Figure 1

Engelbart’s “A Total Program” map from “Augmenting Human Intellect”

Source: Waldrip-Fruin & Montfort, 2003, p. 106)

Current Issues in Education, 22(1)

7

Haymes: Thinking Backward: A Knowledge Network for the Next Century

In order to clearly explain the research program that he is proposing to undertake,

Engelbart breaks free of the constraints of text to illustrate an iterative map forward. “When you

get used to using a network representation like this, it really becomes a great help in getting the

feel for the way all the different ideas and reasoning fit together – that is, for the conceptual

restructuring.” (Waldrip-Fruin & Montfort, 2003, p. 106) Instead of giving us a fixed textual

stream, computers open up the possibility of viewing the relationships in knowledge visually.

For the first time in this diagram we can start to perceive Bush’s trails. Constructing this in 1962

was undoubtedly a manual process but Engelbart was not one to let technology dictate his larger

vision. He clearly saw this as a dynamic possibility because he goes on to say, “It is a lot like

using zones of variable magnification as you scan the structure – higher magnification where you

are inspecting detail, lower magnification in the surrounding field so that your feel for the whole

structure and where you are in it can stay with you.” (Waldrip-Fruin & Montfort, 2003, p. 107)

This is not about inventing mice. It is about opening a gateway to thinking on the level

that Bush demands. It is about abandoning archaic text-based indexing systems for something

more appropriate to a digital vision of the world. It is about creating a visual language as a first

step toward creating a relativistic conceptual language. Engelbart thinks that the old way of

working with information (text) is severely limited and that technological systems might offer

way out of that.

I found, when I learned to work with the structures and manipulation processes

such as we have outlined, that I got rather impatient if I had to go back to dealing

with the serial-statement structuring in books and journals, or other ordinary

means of communicating with other workers. It is rather like having to project

three-dimensional images onto two-dimensional frames and to work with them

there instead of in their natural form. Actually, it is much closer to the truth to say

that it is like trying to project n-dimensional forms (the concept structures, which

we have seen can be related with many many nonintersecting links) onto a one-

dimensional form (the serial string of symbols), where the human memory and

visualization has to hold and picture the links and relationships. I guess that’s a

natural feeling, though. One gets impatient any time he is forced into a restricted

or primitive mode of operation—except perhaps for recreational purposes.

(Waldrip-Fruin & Montfort, 2003, p. 108)

Engelbart articulated this vision almost 60 years ago. Yet “modern” information storage

and retrieval systems, including the current version of the internet developed by Tim Berners-

Lee, have continued to double down on the library indexing model of information sharing. While

there are dynamic linkages, the fundament of the internet’s addressing structure still views sites

as a sequence of pages that metaphorically might as well be stacks of paper on millions of desks.

Sure, it’s nice to have access to all of those desks but, like the warehouse at the end of Raiders of

the Lost Ark, this plethora of information is only useful to the extent that you can connect it up

and recombine it in new ways. The site/page metaphor resists atomic manipulation of its

contents, sometimes implicitly, sometimes explicitly.

Like this journal article itself, the metaphors of text and paper lead us down certain

pathways in understanding the connections between ideas. One of my struggles as its author has

been to pull together a complex web of breadcrumbs into a linear narrative. This skill is

important but at the same time, we have to recognize all that must be discarded for it to be

Current Issues in Education, 22(1)

8

Haymes: Thinking Backward: A Knowledge Network for the Next Century

presented in this form. It serves as a demonstration of how we are forced down linear channels

rather than creating constellations of ideas. Text has limited our tools and these tools have, in

turn, only created to this point opportunities to perceive an exploding universe of text-driven

pathways instead of shifting our larger perceptual paradigms. Without context, information never

becomes knowledge.

Ted Nelson perceived the complexity of knowledge and our limitations in expressing it

early in his life and he has struggled to realize this vision ever since.

It was an experience of water and interconnection […] I was trailing my hand in

the water and I thought about how the water was moving around my fingers,

opening on one side and closing on the other. And that changing system of

relationships where everything was kind of a similar and kind of the same, and yet

different. That was so difficult to visualize and express, and just generalizing that

to the entire universe that the world is a system of ever-changing relationships and

structures struck me as a vast truth. Which it is.

So, interconnection and expressing that interconnection has been the

center of all my thinking. And all my computer work has been about expressing

and representing and showing interconnection among writings, especially. And

writing is the process of reducing a tapestry of interconnections to a narrow

sequence. And this is in a sense elicit. This is a wrongful compression of what

should spread out. (Nelson, as quoted in Werner Herzog’s “Lo and Behold”

[2016], emphasis added)

Decades before, in 1970, Nelson argued that “We do not make important decisions, we

should not make delicate decisions, serially and irreversibly. Rather, the power of the computer

display (and its computing and filing support) must be so crafted that we may develop

alternatives, spin out their complications and interrelationships, and visualize these upon a

screen.” (Waldrip-Fruin & Montfort, 2003, pp. 332) He is arguing that technology should allow

us to design, to see how relationships play out, and to experiment iteratively instead of fixing us

onto a serial path. Our emphasis on tool building must focus on creating Thinkertoys to support

learning and experimentation, not be used to cement fixed paths and relationships.

Some of the facilities that such systems must have include the following:

• Annotations to anything, to any remove

• Alternatives of decision, design, writing, theory

• Unlinked or irregular pieces, hanging as the user wishes

• Multicoupling, or complex linkage, between alternatives, annotations or whatever

• Historical filing of the user’s actions, including each addition and modification,

and possibly the viewing actions that preceding them

• Frozen moments and versions, which the user may hold as memorable for his

thinking

• Evolutionary coupling, where the correspondences between evolving versions are

automatically maintained, and their differences or relations easily annotated

(Waldrip-Fruin & Montfort, 2003, p. 332)

Current Issues in Education, 22(1)

9

Haymes: Thinking Backward: A Knowledge Network for the Next Century

What Nelson is describing here is a dynamic system of relativistic relationships, not a

fixed indexing system in any way. The water may close back around your fingers, but it is

important to understand where you are and were on the sea. It is easy to get lost in the sea of

knowledge and the metaphor of “drowning in information” is completely apropos in this context.

Like Einstein, Bush, Engelbart and Nelson are not rejecting the principles of the rationalist

Newtonian model. Rather, they are arguing that it is no longer sufficient in organizing and

explaining our world. Computers are a tool for taking over the mundane aspects of creating

navigation systems to help us better see relationships. They can provide compasses and

waypoints on the relativistic sea of information they are capable of storing. It is up to us to

perceive the relationships that then become apparent.

For centuries we have had such tools at our disposal, but they were reserved to a narrow

spectrum of artists who had the technical skill to execute them. Art is fundamentally about the

creation of new connections in the world, whether that is in the assemblage of tonal elements

into a new kind of music or the assemblage of visual elements into paintings, photographs, or

films. Computers have significantly lowered the technical barriers to executing thinking on this

level. Both Engelbart and Nelson seem to be pointing us in the direction of using the new

technology to open up new ways of connecting knowledge in ways previously reserved to artists.

Nelson has struggled for decades trying to realize his vision through his Xanadu Project

(http://www.xanadu.net) but he recognizes that at its root even Xanadu is about connecting

textual ideas. Realized to its fullest potential, a Xanadu project for the 21st century would

eliminate the word “text” from that statement and focus on our ability to simply connect “ideas.”

Conclusion: Visual Thinking, Relational Thinking and a Concept for Deep Thought

Engelbart gave us many clues in how to start using technology to shape thought in

“Augmenting Human Intellect” in 1962. One was the thought diagram illustrated previously. His

concepts were connected by a series of fluid relationships rather than being fixed in a linear

textual arrangement. The idea of concept mapping goes back to the 1930s but technical

limitations (it was obviously not a fluid arrangement) limited it to illustrative purposes. Modern

toolsets allow us to start to approach the dynamic kinds of relationships that Bush, Engelbart,

and Nelson seem to have in mind, at least in form if not in substance.

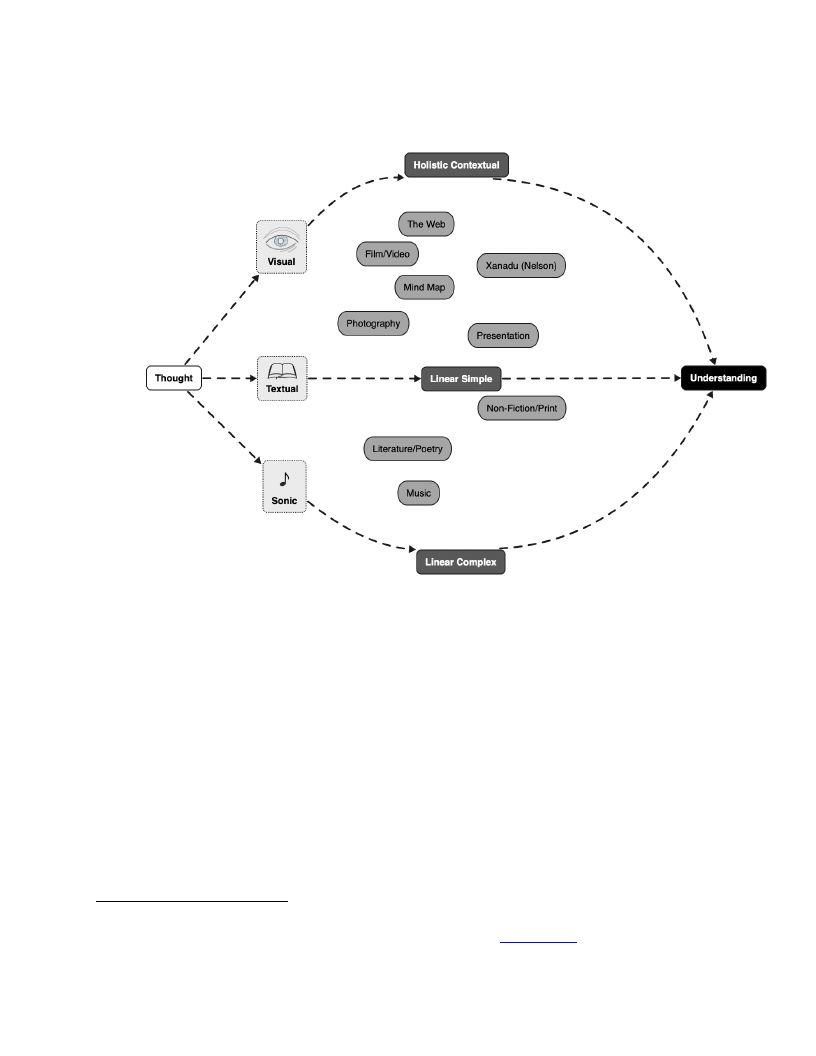

All knowledge is a process of interchange between thought and understanding, whether

that is an internal process or the product of collaboration with others. There are geniuses

throughout history that have instinctually combined many of these elements internally. However,

as thinkers such as Steven Johnson, Frans Johansson, and others have demonstrated, all ideas are

a product of social processes as much as they are of individual inspiration. It is beyond the scope

of this paper to explore that fully. However, what is clear is that process of turning thoughts into

understanding is not always a simple one. Today we have a large variety of tools that can help us

put that into context such as the simple concept mapping tool I used to create this diagram.

Current Issues in Education, 22(1)

10

Haymes: Thinking Backward: A Knowledge Network for the Next Century

Figure 2

From Thought to Understanding, an Example of a Simple Concept Map

It interesting that you can see a train of concept mapping throughout the work of Bush,

Engelbart, and Nelson. What all three thinkers are essentially suggesting this that we may need

to invent a whole new language that effectively combines text and visual elements with a

language of connections. Concept mapping gets us there in form, if not in substance. It is a way

to leverage the dynamic mapping of visual representations of ideas to create new perceptions of

problem sets. I’ve used it for years in brainstorming sessions and have recently introduced it to

my pedagogical repertoire. It adds a second dimension by lifting textual bits of information out

of their linear context and places them into a manipulatable graphic context which adds a second

dimension. Even this simple, one-dimensional hop opens up many new possibilities for exploring

ideas. However, it is not sufficient in and of itself.

Concept mapping lacks depth. It is the difference between going from a line to a canvas.

However, most of the emergent challenges we have been discussing throughout this work have

additional dimensions of depth and time that a conceptual map still struggles to represent.1 As

such, concept mapping and visual thinking can represent extremely important new tools for

breaking free from linear, textual thinking. They allow us to reimagine our informational

connections and can represent accessible explorations of those connections. However, concept

1 Virtual reality might be a possible tool capable of providing a bridge for visualizing data in a dynamic

concept mapping environment. An interesting first step might be the Noda Project. However, the step of

seamlessly linking this to a robust information network is still missing here.

Current Issues in Education, 22(1)

11

Haymes: Thinking Backward: A Knowledge Network for the Next Century

mapping usually fails to document or capture the intervening journey of how those connections

are formed, which is a key element of the vision originally articulated by Bush in 1945. For this,

we need to build something far more conceptually ambitious.

As is often the case, science fiction may provide us with an important conceptual insight.

Douglas Adams created the supercomputer Deep Thought as a key plot point to his series The

Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. In the novel Deep Thought was created to provide the answer

to “life, the universe, and everything.” After gestating on the answer for 7 ½ million years, the

computer responded with the enigmatic “answer” of “42.” When its creators expressed

consternation over the answer it replied, “I think the problem, to be quite honest with you, is that

you’ve never really known what the question is” (Adams, 1989, p. 121).

The entirety of the Hitchhikers Guide saga is spent searching for an elusive question as if

it were an answer. This is a perfect metaphor for the open-ended kinds of questions we need to

harness our knowledge network to engage, not answer. There is no ultimate answer to

democracy, climate change, poverty, or augmenting human intellect. These are questions that

will challenge humanity until the next great paradigmatic shift and beyond. We need to develop

systems to manage our engagement with these questions. Our Newtonian knowledge systems are

not up to the task for they seek answers instead of questions. This does not mean that we should

stop seeking answers but that we have to expand our mental universe to accept that some

questions, like that of “life, the universe, and everything,” simply do not have answers.

This is a level of abstraction that is at least two steps removed from magical thinking,

which is often our natural state. Magical thinking relies on a faith in one set of answers. Rational

thinking relies on faith in a fixed set of rules that will lead us to answers. Relativistic thinking

plays with those rules to perceive entirely new sets of solutions but accepts that these may not

represent final “answers” and considers the possibilities that the rules themselves may need to be

questioned. Our intellectual tools need to be adapted to that purpose. We made tools to overcome

gravity and fly. Now we need tools to overcome our mental limitations and accept ambiguity and

an evolving emergent future.

A 21st century Deep Thought system would allow us to explore ideas more dynamically

with a vast amount of data at our disposal. In other words, it’s a system designed to facilitate

connections between varied and abstract pieces of data. Once again, Engelbart provides us with a

vision for how this might be done. In the 1980s and 1990s Douglas Engelbart was not working

on new and improved versions of the mouse. His ongoing frustration with peoples’ seeming

inability to grasp the deeper purpose of the work he was doing at SRI in the 1960s led him into

organizational thinking (Rheingold, 2000). As part of his “Bootstrap Strategy,” now carried on

by his daughter Christina at the Engelbart Institute, he developed the concept of “Networked

Improvement Communities.”

An improvement community that puts special attention on how it can be

dramatically more effective at solving important problems, boosting its collective

IQ by employing better and better tools and practices in innovative ways, is a

networked improvement community (NIC).

If you consider how quickly and dramatically the world is changing, and

the increasing complexity and urgency of the problems we face in our

communities, organizations, institutions, and planet, you can see that our most

urgent task is to turn ICs into NICs.

(http://www.dougengelbart.org/content/view/191/268/)

Current Issues in Education, 22(1)

12

Haymes: Thinking Backward: A Knowledge Network for the Next Century

We already have semi-functioning Networked Improvement Communities, but they lack

critical conceptual and communication tools. At a local level, as Engelbart points out,

Improvement Communities have functioned for centuries. The coffee houses of Europe,

particularly England, have been highlighted by Steven Johnson and others as central to the

incubation of the Enlightenment (Johnson, 2010). Expanding this on a global scale, however,

remains an ongoing challenge, as Networked Improvement Communities such as ShapingEDU

demonstrate.

Turning ICs into NICs requires a complementary technology, the Dynamic Knowledge

Repository. The Engelbart Institute describes DKRs as:

A dynamic knowledge repository is a living, breathing, rapidly evolving

repository of all the stuff accumulating moment to moment throughout the life of

a project or pursuit. This would include successive drafts and commentary leading

up to more polished versions of a given document, brainstorming and conceptual

design notes, design rationale, work lists, contact info, all the email and meeting

notes, research intelligence collected and commented on, emerging issues,

timelines, etc. (http://www.dougengelbart.org/content/view/190/163/)

We have vast databases that store and index data but these are often technically divorced

from our communities. The tools are simply not there to create an ongoing and dynamic

relationship between the information and network. This is because those databases are not

Dynamic Knowledge Repositories. They are fundamentally designed around text-based indexing

systems that Bush rejected as inadequate 75 years ago. As a consequence, modern databases do

not effectively “record exchanges,” as Engelbart put it, at least not in the sense of knowledge.

Like many technologies today we are missing that critical connection between the vast amounts

of information stored in databases and the human processes needed connect that information into

actionable knowledge.

Deep Thought is conceptually a “Dynamic Knowledge Repository.” At its root it would

be designed to connect data to form new sets of questions, and therefore knowledge. Using

principles of “Emergent Design” as recently described in Ann Pendleton-Jullian’s and John

Seely Brown’s excellent Design Unbound (2018), the project would create a wide range of tools

based on visual mapping to create a truly dynamic database tool designed to support a wide

variety of Networked Improvement Communities. This toolset will be explicitly designed to

dynamically grow and change as circumstances demand. Tools such as Augmented Reality,

Virtual Reality, and blockchain (for authentication, not sequestering information) would form

valuable adjuncts in helping us to visualize knowledge in completely new and dynamic ways.

Instead of replacing human thought processes Artificial Intelligence would be employed to guide

us to potentially interesting patterns in connections and knowledge that reside in the intersections

between traditional disciplines.

The Deep Thought concept can trace its roots back to Bush via Engelbart and Nelson.

However, it is also deeply rooted in the history of ideas. The Enlightenment was sparked by a

flurry of intellectual activity in the late 17th century in Europe by the network of ideas embodied

by “The Republic of Letters.” Its correspondence formed a Dynamic Knowledge Repository for

the Networked Improvement Community created by its scientists and thinkers. This networked

community helped to plot a way out of the religious wars brought about in part by the invention

of the printing press two centuries earlier.

Current Issues in Education, 22(1)

13

Haymes: Thinking Backward: A Knowledge Network for the Next Century

“[The Republic of Letters] was an institution perfectly adapted to disruptive change of

unprecedented proportions. Its history raises the question of why Europe’s diversity

brought progress in scholarship when by rights disunity ought to have crippled it. The

answer is as simple as it is radical: with existing institutions of learning in crisis or

collapse, the Republic of Letters founded its legitimacy on the production of new

knowledge.” (McNeely & Wolverton, 2008, p. 123)

The internet is the printing press of our age. We find ourselves at a new crossroads lost in

a sea of information. Vannevar Bush may have perceived this challenge earlier than most, and

Douglas Engelbart and Ted Nelson busied themselves in solving the technical challenges it

represented, but we still find ourselves in the place that they warned us about. Society is once

again in danger of becoming unstuck from its informational anchors. In the 1500s this resulted in

more than a century of bloodshed. We have it in our power to bypass that fate, fast forward 200

years, and create a digital Republic of Letters. By combining the best of what text offers with the

new vocabulary of digital tools now at our disposal, we must finally create systems that augment

how we really think.

References

Adams, D. (1989). The more than complete hitchhiker’s guide. Random House.

Doug Engelbart Institute. (n.d). Doug Englebart Institute. http://www.dougengelbart.org

Herzog, W. (Director). (2016). Lo and behold, reveries of the connected world. [Documentary].

NetScout.

Johansson, F. (2006). The Medici effect. Harvard Business School Press.

Johnson, S. (2010). Where good ideas come from. Penguin.

McNeely, I. F., & Wolverton, L. (2008). Reinventing knowledge: From Alexandria to the

Internet. W.W. Norton.

Rheingold, H. (2000). Tools for thought (2nd ed.). MIT Press.

Pendleton-Jullian, A., & Seely Brown, J. (2018). Design unbound. MIT Press.

Sagan, C. (1997). The demon-haunted world: Science as a candle in the dark. Ballantine.

Shlain, L. (1993). Art & physics: Parallel visions in space, time, and light. HarperCollins.

Waldrip-Fruin, N,, & Montfort, N. (Eds.) (2003). The new media reader. [print ed.]. MIT Press.

Online version available at https://archive.org/details/TheNewMediaReader

Current Issues in Education, 22(1)

14

Haymes: Thinking Backward: A Knowledge Network for the Next Century

Tom Haymes

Ideaspaces, Founder

tom@ideaspaces.net

Author Notes

Guest Editor Notes

Sean M. Leahy, Ph.D.

Arizona State University, Director of Technology Initiatives

sean.m.leahy@asu.edu

Samantha Adams Becker

Arizona State University, Executive Director, Creative & Communications, University

Technology Office; Community Director, ShapingEDU

sam.becker@asu.edu

Ben Scragg, MA, MBA

Arizona State University, Director of Design Initiatives

bscragg@asu.edu

Kim Flintoff

Peter Carnley ACS, TIDES Coordinator

kflintoff@pcacs.wa.edu.au

Current Issues in Education, 22(1)

15

Haymes: Thinking Backward: A Knowledge Network for the Next Century

Volume 22, Issue 1

DATE

ISSN 1099-839X

Readers are free to copy, display, and distribute this article, as long as the work is attributed to the

author(s) and Current Issues in Education (CIE), it is distributed for non-commercial purposes only, and no alteration

or transformation is made in the work. More details of this Creative Commons license are available at

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/. All other uses must be approved by the author(s) or CIE. Requests

to reprint CIE articles in other journals should be addressed to the author. Reprints should credit CIE as the original

publisher and include the URL of the CIE publication. CIE is published by the Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College at

Arizona State University.

Editorial Team

Consulting Editor

Neelakshi Tewari

Lead Editor

Marina Basu

Section Editors

L&I – Renee Bhatti-Klug

LLT – Anani Vasquez

EPE – Ivonne Lujano Vilchis

Review Board

Blair Stamper

Melissa Warr

Monica Kessel

Helene Shapiro

Sarah Salinas

Faculty Advisors

Josephine Marsh

Leigh Wolf

Current Issues in Education, 22(1)

16