AFRREV VOL 14 (1), S/NO 57, JANUARY, 2020

African Research Review: An International

Multidisciplinary Journal, Ethiopia

AFRREV Vol. 14 (1), Serial No 57, January, 2020: 1-16

ISSN 1994-9057 (Print) ISSN 2070-0083 (Online)

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/afrrev.v14i1.1

Reducing Old Age Vulnerabilities in Developing Countries: The Role

of Income-Support on Poor Older People’s Health

Awojobi, Oladayo Nathaniel

Department of Social Security

Bonn-Rhein-Sieg University of Applied Sciences

Sankt Augustin, Germany

E-mail: dawojobi@gmail.com

Phone: +4915215820100

Abe, Jane Temidayo

Department of Psychology

Nnamdi Azikiwe University

Awka, Anambra State, Nigeria

E-mail: temidayojabe@gmail.com

Phone: +2348062849579

Abstract

This systematic review is on the impact of income-support on older people’s health in

developing countries. A systematic search for non-randomised and mixed methods studies

published between 2013 and 2017 was conducted in academic and grey literature databases,

websites and references lists of relevant studies. Study methodological quality was assessed

with a risk of bias tool. Inclusion criteria were met by 7 studies, 3 in Latin America, two each

in Africa and Asia. Five of the studies used a quantitative non-randomised approach while the

remaining two used mixed methods analysis. Income-support was discovered to have positive

effects on older people’s nutritional status, cognitive functions, health and psychological

wellbeing. Income-support offers older people access to healthcare services and protection

against detrimental effects of lack of money in accessing healthcare services.

Key Words: Health, income-support, older people

COPYRIGHT © IAARR: https://www.afrrevjo.net

1

Indexed African Journals Online: www.ajol.info

Indexed Society of African Journals Editors (SAJE); https://africaneditors.org/

AFRREV VOL 14 (1), S/NO 57, JANUARY, 2020

Introduction

The population of older people in developing countries is increasing. For instance, it has been

projected that by the year 2050, the ageing population in sub-Saharan Africa would have

increased to 161 million (Aboderin& Beard, 2015; Audain, Carr, Dikmen, Zotor, &Ellahi,

2017; Nanyonjo, 2016; UN, 2016). Most of the health systems in developing countries are

not prepared adequately for the health demands of older people (HelpAge International,

2017). There are inadequate health facilities specializing on older people’s health as facilities

are not designed to the older people’s medical needs and personnel are not properly trained in

administering care to them (HelpAge International, 2017).

The majority of the older people in developing countries do not have health insurance where

most of the health services are the cash-and-carry systems that mandated patients, even those

brought to the hospital on emergencies to pay cash deposit at every point of service

delivery (HelpAge International, 2017). Also, available data showed that less than 17% of

older people have pensions in sub-Saharan Africa (UN, 2016). Because of this, older people

in the region continue to work on the farms to earn a living (Aboderin& Beard, 2015; UN,

2016). Aside from remaining part of the labour force beyond the stipulated recommended age,

older people in sub-Saharan Africa whose adult children have moved to other cities in search

of work or have died for one reason or the other, also take care of their grandchildren

(Aboderin & Beard, 2015; UN, 2016).

Planning for an ageing population is crucial to the attainment of the integrated 2030 Agenda,

with ageing running across the goals of poverty reduction, good health, economic growth,

gender equality and decent work (Dugarova, 2017). Ghana is one of the leading countries in

sub-Saharan Africa that have taken the initiative to support older people. The government, in

2008, introduced the Livelihood Empowerment Against Poverty (LEAP), a cash transfer

programme for older people of 65 years and above who are considered extremely poor and

live in vulnerable households.

There is increasing empirical evidence pointing to considerable degrees of functional

impairment among older people, partially connected to the protracted disease

burden (Nanyonjo, 2016). It has been reported that older people in developing countries are

prone to a lot of diseases, both communicable and non-communicable ones. Such diseases

include cardiovascular and circulatory disease, cancer, diabetes, cirrhosis of the liver and

nutritional deficiencies (Aboderin& Beard, 2015; Audain et al., 2017; Nanyonjo, 2016; UN,

2016). Furthermore, a survey of older people in Africa showed high levels of “hypertension,

musculoskeletal disease, visual impairment, functional limitations and depression” (Aboderin

& Beard, 2015, p.10). Additionally, contagious illnesses continue to affect older women and

men in sub-Saharan Africa, highlighted by a significant prevalence of HIV infection and its

worsening effect on various non-communicable diseases (Aboderin & Beard, 2015).

Since disease burden increases with age, there is a huge need for the prevention and treatment

of these diseases and long-term care for older people in developing countries (Nanyonjo,

2016; UN, 2016). Studies have shown that older people in developing countries face a

herculean task in accessing healthcare services because of transport cost and the cost of

paying for healthcare services (Aboderin& Beard, 2015; HelpAge International, 2017).

Therefore, social pension interventions or similar interventions for income support to older

people in developing countries are important to the social security of older people (UN,

2016).

COPYRIGHT © IAARR: https://www.afrrevjo.net

2

Indexed African Journals Online: www.ajol.info

Indexed Society of African Journals Editors (SAJE); https://africaneditors.org/

AFRREV VOL 14 (1), S/NO 57, JANUARY, 2020

Evidence has shown that income-support plays a crucial role in removing some demand-side

obstacles, such as out-of-pocket expenditures to healthcare for older people (HelpAge

International, 2017). It has also been reported that older people use income-support for

transporting themselves to health facilities, consultation fees and treatment cost as well as

health insurance and prescriptions (HelpAge International, 2017). The general impact of

income-support on older people's health-outcomes in developing countries is not yet fully

known as limited research has been done in this area. For instance, the field of research on

older people's health in sub-Saharan Africa is still at an early stage (Nanyonjo, 2016).

Additionally, limited attention has been given to issues of older people in sub-Saharan Africa,

which remains the earth’s poorest and youngest region (Aboderin& Beard, 2015).

There is the need for a better understanding of the health challenges of older people, their

limited access to health facilities and the crucial role income-support is playing in removing

some demand-side barriers to healthcare services. This review aims to assess the impact of

income-support on older people’s health.

Materials and Methods

Criteria for Considering Studies for the Review

Type of studies

This review aims to assess the impact of income-support on older people’s healthcare. In

order to accomplish the aim of the review, we focused on studies in developing countries that

evaluate the effects of income-support programmes on older people’s health. In a nutshell, we

considered studies that focused on the role of income-support in assisting older people to

access healthcare services. The following study designs were used for the review:

• Quasi experimental design

• Mixed methods

• Cross sectional study

• Quantitative non-randomised

Types of participants

This review included studies that assess the interface between income-support and the health

of older people of the ages of 60 and above in developing economies as defined by the United

Nations (UN, 2014).

Types of interventions

This review included income programmes that were meant to reduce poverty and

vulnerabilities in poor households with older people of 60 years and above. That is, to be

included in this review, interventions must meet the following criteria:

• a non-conditional cash transfer to older people;

• income supplement for poor elderly in low- and middle-income setting;

• old age grants for older people’s wellbeing;

• old age allowance for older people with income not more than USD 35.52 annually;

• social pension to provide minimum income for old age; and

• conditional cash transfer to support vulnerable older people.

Types of outcome measures

COPYRIGHT © IAARR: https://www.afrrevjo.net

3

Indexed African Journals Online: www.ajol.info

Indexed Society of African Journals Editors (SAJE); https://africaneditors.org/

AFRREV VOL 14 (1), S/NO 57, JANUARY, 2020

This review included studies that estimated the impact of income-support programmes on

older people’s health and changes in health outcomes. These outcomes are divided into

primary and secondary outcomes measured by the included studies.

Primary outcomes

The following primary outcomes were eligible for the review:

• Use of healthcare services, including but not limited to:

➢ doctor consultation;

➢ outpatient visits;

➢ purchasing of drugs;

➢ transportation cost to healthcare facilities;

➢ treatment of ailments;

➢ use of cash transfers in removing any demand-side barriers to healthcare

services.

• Health outcomes, but not limited to:

➢ cognitive functions;

➢ food security;

➢ improvement in lung functions;

➢ mental wellbeing;

➢ reduction in depressive symptoms.

Secondary outcomes

This review considered the following as the secondary outcomes:

• social determinant of health;

• healthcare expenditure;

• changes in access to healthcare services.

Search Methods for Identification of Studies

We conducted an electronic search for relevant studies for the systematic review. The

searches were conducted in the following databases which included both academic and grey

literature:

• PubMed

• Cochrane Library

• ResearchGate

• African Journals Online

• Google Scholar

• African HealthLine

• HelpAge International Social Pension Database

• Science Direct

• Cambridge Journal Database

• Oxford Journal Database

Aside from the use of electronic search for the selected studies of this review, we searched the

websites of prominent organisations such as the WHO, HelpAge International, World Bank,

USAID and the UK Department of International Development (DFID). We conducted an

COPYRIGHT © IAARR: https://www.afrrevjo.net

4

Indexed African Journals Online: www.ajol.info

Indexed Society of African Journals Editors (SAJE); https://africaneditors.org/

AFRREV VOL 14 (1), S/NO 57, JANUARY, 2020

additional search on the reference lists of the included studies in case we have missed any

relevant literature from the electronic search.

Data collection and Analysis

Selection of studies

The two authors were responsible for the selection of relevant studies for the review which

was done independently. The disagreements that emanated from the selection process were

resolved through discussion among the authors. Initially, we screened the titles of the selected

studies and through this process duplicate records were removed. A second round of

screening was done on the titles and abstracts of the selected studies in order to identify

studies that meet the inclusion criteria of the review. An additionally screening of abstracts

and full text of the selected studies paved way for the identification of studies that were

eligible for the review.

Data extraction and management

Data were extracted independently from studies included in this systematic review by the two

authors, (O.A.& J.A.) using the standardised data extraction tool available in JBI SUMARI

(Aromataris& Munn, 2017). Data extracted included the following:

• Author’s names

• Publication date

• Geographical region

• Types of study

• Data collection methods

• Participants

• Interventions

• Main outcome measures and results

Quality assessment

Two authors (O.A and J.A) independently assessed the quality of the included studies. During

this process, the disagreements that emanated were resolved through discussion. To assess

the risk of bias of the included studies, we employed the Mixed Method Appraisal Tool

(MMAT) prepared by (Hong et al., 2018). The risk of bias was assessed by the following

scores: Yes, No and Cannot tell, while the overall appraisal of the risk of bias for the included

studies that was used for the summary assessment were as follow: Include, Exclude, and

Seek further info.

Data synthesis

Due to the heterogeneity in study setting, design, interventions and outcomes mentioned in

the included studies, it was not feasible to statistically combine the results of the studies under

review. In this case, we used qualitative synthesis vis a vis narrative synthesis to present the

estimated effects of income-support on older people’s health from the included studies.

Results

Study Selection

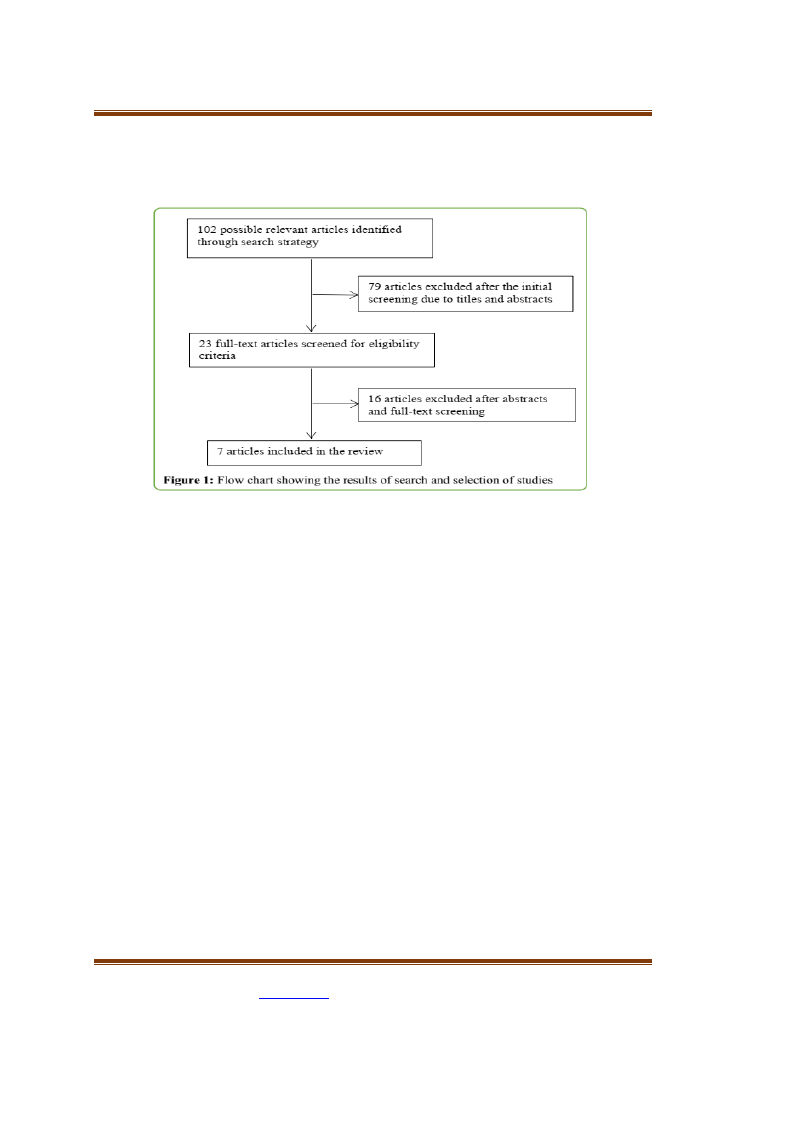

Figure 1 presents the study selection process for the systematic review. Our initial search for

relevant literature produced 102 articles. Due to the screening of titles and abstracts of the

COPYRIGHT © IAARR: https://www.afrrevjo.net

5

Indexed African Journals Online: www.ajol.info

Indexed Society of African Journals Editors (SAJE); https://africaneditors.org/

AFRREV VOL 14 (1), S/NO 57, JANUARY, 2020

initial identified articles, 79 articles were excluded, leaving 23 articles for full text screening.

The 23 articles were screened for eligibility through abstracts and full text, leaving only 7

articles for the final review.

Characteristics of the Included Studies

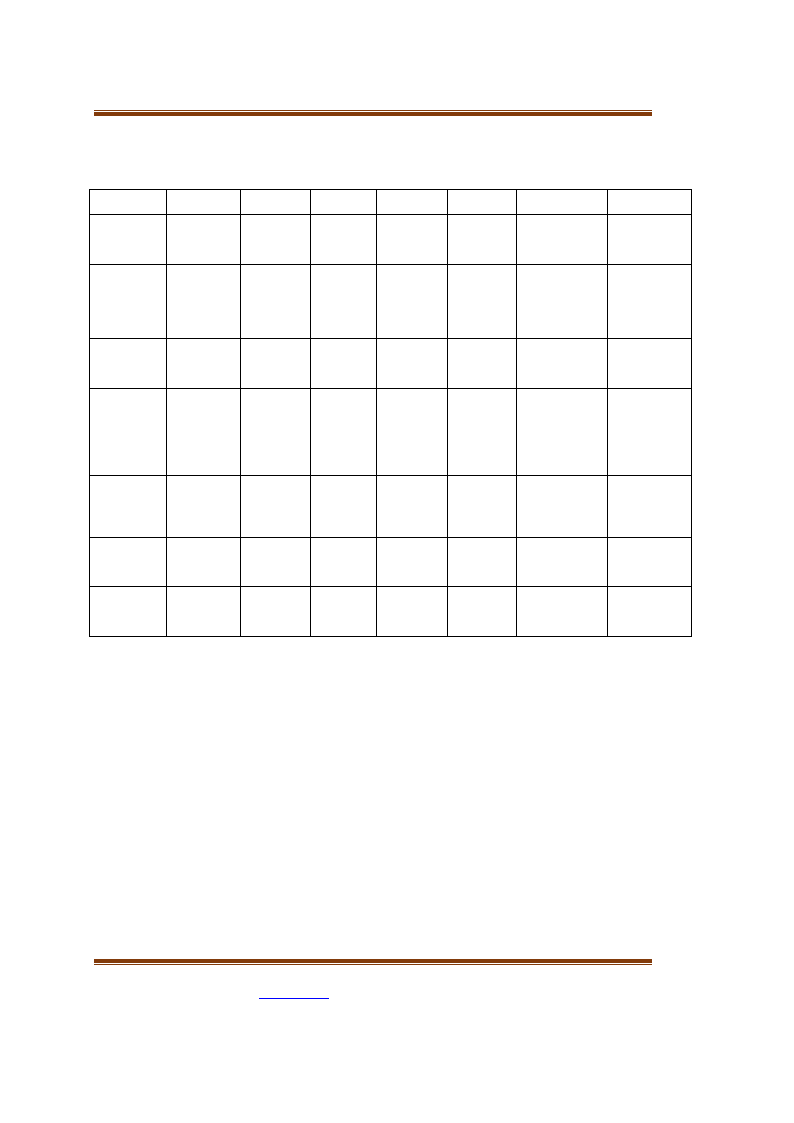

Table 1 shows the characterises of the seven included studies. Geographically, three of the

studies were conducted in Latin America: Mexico (Aguila, Kapteyn, and Smith, 2015;

Salinas-Rodríguez and Manrique-Espinoza, 2013; Salinas-Rodríguez, Torres-Pereda,

Manrique-Espinoza, Moreno-Tamayo, and Téllez-Rojo Solís, 2014); two were conducted in

Asia: Bangladesh (Uddin, 2013) and China (Cheng, Liu, Zhang, and Zhao, 2018); and the

remaining studies were conducted in sub-Saharan Africa: Ethiopia, Mozambique, Tanzania

and Zimbabwe (HelpAge International, 2017) and South Africa (Lloyd-Sherlock and

Agrawal, 2014).

In terms of study design, four studies used non-randomised approach (Aguila et al., 2015;

Cheng et al., 2018; Lloyd-Sherlock and Agrawal, 2014; Salinas-Rodríguez et al., 2014), two

others used mix methods technique (HelpAge International, 2017; Uddin, 2013) and one used

cross sectional (Salinas-Rodríguez and Manrique-Espinoza, 2013). The included study types

composed of four peer-reviewed articles (Aguila et al., 2015; Lloyd-Sherlock Agrawal, 2014;

Salinas-Rodríguez and Manrique-Espinoza, 2013; Salinas-Rodríguez et al., 2014), one

discussion paper (Cheng et al., 2018), one dissertation (Uddin, 2013) and one grey literature

(HelpAge International, 2017).

In terms of intervention, most of the studies focused on cash transfers and social pension.

Data used by the included studies in estimating the effects of income-support on older

people’s health were sourced from different sources such as interview, longitudinal survey

and focus group discussion. Outcomes measured by the included studies include health

benefits, physical health, mental health, vaccination and access to healthcare services.

COPYRIGHT © IAARR: https://www.afrrevjo.net

6

Indexed African Journals Online: www.ajol.info

Indexed Society of African Journals Editors (SAJE); https://africaneditors.org/

AFRREV VOL 14 (1), S/NO 57, JANUARY, 2020

Table 1: Characteristics of the includedstudies

Authors

Date

Aguila et al.

(2014)

Cheng et al.

(2016)

HelpAge

International

(2017)

Lloyd-

Sherlock and

Agrawal

(2014)

Salinas-

Rodríguez and

Manrique-

Espinoza

(2013)

Salinas-

Rodríguez et

al.(2014)

Uddin (2013)

Country

Mexico

China

Ethiopia,

Mozambique,

Tanzania and

Zimbabwe

South Africa

Mexico

Mexico

Bangladesh

Study

design

Quasi-

experimental

Non-

randomised

Mixed

methods

Non-

randomised

Cross-

sectional

Non-

randomised

Mixed

methods

Type of

study

Peer-

reviewed

Discussion

paper

Grey

literature

Peer-

reviewed

Peer-

reviewed

Peer-

reviewed

Dissertation

Intervention

Income

supplement

Social

pension

Cash

transfers

Social

pension

Conditional

cash transfer

Non-

contributory

social

pension

Old-age

allowance

Participant

Seventy-

year and

above

Elderly

population

aged 60 and

above

158 elderly

people

Black

African

women aged

60 and over

and men

aged 63 and

over

12,146 older

people

5,270 older

adults

40

programme

beneficiaries

Data source

Rich data

capturing health

and wellbeing in

old age

Chinese

Longitudinal

Healthy

Longevity

Survey

(CLHLS)

Focus group

discussion,

interview

World Health

Organization

(WHO) survey of

Global Ageing

and Adult Health

(SAGE)

2007

Oportunidades

Evaluation

Survey

Baseline and

follow-up survey

Data from

primary and

secondary

sources

Outcomes

measured

Health benefits

Physical health,

cognitive

function, and

psychological

well-being

Access to

healthcare

services

Health service

utilisation,

hypertension

awareness and

treatment

Vaccination

coverage

Mental

wellbeing

Access to

healthcare

facilities

Methodological Quality of Included Studies

We used MMAT risk of bias tool to assess the methodological quality of the included studies

(Hong et al.,). The quality of the five quantitative studies included in the review was high

because each of the study scored the following grades 5/5; (Lloyd-Sherlock and Agrawal,

2014); 4/5 each for (Aguila, Kapteyn, & Smith, 2015; Cheng et al., 2018; Salinas-Rodríguez

and Manrique-Espinoza, 2013; Salinas-Rodríguez et al., 2014) from the methodological

quality criteria. All the study measurements were appropriate for both their outcomes and

interventions and their study participants were representative of the target population.

The quality of two of the mixed method studies was moderate, as each of the study scored 3/5

(HelpAge International, 2017; Uddin, 2013) from the methodological quality criteria. The two

studies showed adequate rationale for using mix methods design to address the research

question. The different components of the studies were adequately integrated to answer the

research question and the outputs of the combination of the qualitative and quantitative

components were effectively interpreted.

COPYRIGHT © IAARR: https://www.afrrevjo.net

7

Indexed African Journals Online: www.ajol.info

Indexed Society of African Journals Editors (SAJE); https://africaneditors.org/

AFRREV VOL 14 (1), S/NO 57, JANUARY, 2020

Effects of Interventions

Impact on Anthropometric or Nutritional Outcomes

Of the seven studies we reviewed, three reported on the role of income-support programmes

on poor older people’s anthropometric or nutritional status (Aguila et al., 2015; Cheng et al.,

2018; HelpAge International, 2017). In China, social pension enrolment had positive and

significant impact on older people’s height as they experienced 3.5 cm less height shrinkage

than poor older people not receiving social pensions (Cheng et al., 2018). Similarly, a 100

percent rise in pension income had a significant effect on height loss reduction by 0.8 cm

(Cheng et al., 2018). In sum, the social pensions had a positive effect on the physical health of

older people (Cheng et al., 2018). In Ethiopia, cash transfers improved nutrition and food

security for older people (HelpAge International, 2017). According to one of the female

respondents from the focus group discussion:

We used to have one or two meals but now we have three meals. We are also

able to buy vegetables and onions and buy meat twice a month to vary the

diet. We can also buy soap to wash our clothes and utensils and wash clothes

for our children and grandchildren. I feel stronger and more energetic than

before... I am sure I even look more beautiful(HelpAge International, 2017,

p. 23).

In Mexico, income supplementation on the health of poor older people showed that little

segment of the older people receiving income supplement reported that they ran out of food

stuff in the last three months compared to poor older people not receiving income

supplementation (Aguila et al., 2015). In addition, the treatment group reported a significant

decrease of being hungry and not eating all day compared to the control group (Aguila et al.,

2015).

Impact on Cognitive Functions

Two studies of the seven studies we reviewed reported on the interface between income-

support and older people’s cognitive functions (Aguila et al., 2015; Cheng et al., 2018). In

China, the take-up of social pensions had a positive effect on the cognitive functions of older

people (Cheng et al., 2018). The findings of the study revealed that enrolment in the pension

programme significantly improved Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score by more

than 2 points and raised the probability of excellent cognitive function by 18 percentage

points (Cheng et al., 2018). Additionally, a 100 percent increase on the social pension benefits

led to a 0.57-point rise in MMSE score, 4.2 percentage points more beneficiaries having

excellent cognitive function (Cheng et al., 2018).

In Mexico, the study of Aguila et al. (2015), using DID estimates to carry simple exercise on

older people’s cognitive function showed that they regressed the health conditions on age and

age squared taking cognisance of peak flow, immediate and delayed recall. Their findings

revealed a marked reduction with age. In continuation of their analysis, they interviewed a 78-

year-old individual in their study sample to know if the income supplement enhances his

health and how much younger the older individual has to be to enjoy the same level of health

in the case of no income supplement. Their findings showed that improvement in immediate

recall was the same as if the study individual were about 5.5 years younger. In the case of

delayed recall, the improvement was tantamount to being 12.4 years younger. For peak flow,

the improvement was commensurate to being 7 years younger (Aguila et al., 2015).

COPYRIGHT © IAARR: https://www.afrrevjo.net

8

Indexed African Journals Online: www.ajol.info

Indexed Society of African Journals Editors (SAJE); https://africaneditors.org/

AFRREV VOL 14 (1), S/NO 57, JANUARY, 2020

Impact on Health Outcomes

Four studies reported health outcomes due to cash transfers on older people (Aguila, Kapteyn,

and Smith, 2015; Cheng et al., 2018; HelpAge International, 2017; Lloyd-Sherlock and

Agrawal, 2014). In China, social pension enrolment by older people led to a significant

reduction in the incidences of hypertension by 21 percentage points and enhanced their

instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) performance by 11 percentage points (Cheng et

al., 2018). Additionally, a 100-percent rise in pension income significantly reduced the

probability of experiencing hypertension by 5.4 percentage points and significantly enhanced

the probability of performing IADL by 2.4 percentage points (Cheng et al., 2018). However,

both the enrolment and increase in pension income by older people have no significant effect

on self-reported general health (Cheng et al., 2018).

The study that investigated the impact of cash transfers on older people’s access to healthcare

services in Ethiopia, Mozambique, Tanzania and Zimbabwe revealed that older people in

these countries faced obstacles in accessing healthcare services because of their economic

conditions. Aside from this, the older people in the study sample from the four countries

reported being affected by non-communicable diseases such as arthritis (Ethiopia 40%;

Mozambique 75%; Tanzania 33%; Zimbabwe 21%); asthma (Ethiopia 11%; Mozambique

12%; Tanzania 9%; Zimbabwe N/A); diabetes (Ethiopia 10%; Mozambique N/A; Tanzania

10%; Zimbabwe 5%); eye problems (Ethiopia 30%; Mozambique 38%; Tanzania 39%;

Zimbabwe 15%); and hypertension (Ethiopia 20%; Mozambique 40%; Tanzania 29%;

Zimbabwe 16%) (HelpAge International, 2017). Despite the cash transfers being recognised

as not being enough to meet the health needs of older people, they were successful in

improving the older people’s abilities to identify and act on their health needs because they

were associated with health awareness activities in Ethiopia and Tanzania (HelpAge

International, 2017).

In Mexico, empirical evidence showed that older people living in Yucatan who received

income supplement had a statistically significant improvement in both immediate and delayed

recall coupled with improvement in lung function measured by peak flow (Aguila et al.,

2015). Additionally, the income supplement helped poor older beneficiaries to have little

presence of low haemoglobin levels linked to fatigue. This effect was marginally significant

to the conventional P value but not significant when Holm-Bonferroni correction was applied

(Audain et al., 2017). In South Africa, poor black older people receiving social pension had a

significant pension status associated with awareness of hypertensive status (OR:2.80; 95%

CI:1.68-4.67), but rural setting was significantly associated with lower awareness (0.61; 95%

CI:0.45-0.82) (Lloyd-Sherlock and Agrawal, 2014)

Impact on Psychological Wellbeing

Three studies reported outcomes on psychological wellness for poor older people after

receiving cash income-support (Cheng et al., 2018; HelpAge International, 2017; Salinas-

Rodríguez et al., 2014). The results obtained in China showed that social pension uptake had

negative and statistically significant result for depression index while a 100-percent increase

in pension income had 0.30 percentage points reduction in depression index (Cheng et al.,

2018). These indicated that the social pension has improved the psychological wellbeing of

the poor older people receiving it (Cheng et al., 2018). The analysis of cash transfer

programmes in Ethiopia, Mozambique, Tanzania and Zimbabwe showed positive effects

despite the little amount of cash receipts given to poor older people (HelpAge International,

COPYRIGHT © IAARR: https://www.afrrevjo.net

9

Indexed African Journals Online: www.ajol.info

Indexed Society of African Journals Editors (SAJE); https://africaneditors.org/

AFRREV VOL 14 (1), S/NO 57, JANUARY, 2020

2017). Evidence showed significant effects of cash transfers allowing older people to better

meet their basic needs, especially in buying different types of food stuff, and hygiene

products. Participants of the focus group discussions in the four countries reported that a large

amount of their cash transfers were spent on food and soap. In Mozambique, cash transfers

were spent in accessing potable water (Salinas-Rodríguez et al., 2014). According to one of

the key informants interviewed in Ethiopia: “Cash transfers also improve the psychology and

self-esteem of the family and the elderly people in particular – the more they secure their

livelihoods, the more they are socially included”(HelpAge International, 2017, p. 23).

The evaluation of Mexican non-contributory social pension scheme showed that after one-year

exposure to the scheme, the beneficiaries’ depressive symptoms significantly decreased (β =

20.06, CI95% 20.12; 20.01) (Salinas-Rodríguez et al., 2014). Similarly, the social intervention

contributed to higher feelings of safety and welfare linked with reduced depressive symptoms

among poor older people (Salinas-Rodríguez et al., 2014). According to some of the

statements of the old beneficiaries of the social intervention, they experienced a decrease or

relief of poverty and stress associated with lack of income and an expanded sense of social

security and wellbeing from receiving monthly income that they could regard their own and

on which they can decide what to do (Salinas-Rodríguez et al., 2014). One of the older

recipients of the social intervention stated:

Now I eat better, now I have ‘a cent’ to buy at least a piece of meat,

something like that… some bread. Before, it was not like this. we couldn’t

buy anything because we did not have money (laughter), and now, yes now,

we have this. I do feel better (Salinas-Rodríguez et al., 2014, p. 6).

Impact on Uptake of Healthcare Services

Six studies reported on the uptake of healthcare services by poor older people due to cash

transfer in their possession (Aguila et al., 2015; HelpAge International, 2017; Lloyd-Sherlock

and Agrawal, 2014; Salinas-Rodríguez and Manrique-Espinoza, 2013; Salinas-Rodríguez et

al., 2014; Uddin, 2013). In Bangladesh, a mixed-method analysis showed that prior to the

introduction of old age allowance, poor older people access healthcare services through the

support of their family members (Uddin, 2013). However, with the introduction of the old age

allowance, 97.5% of the study sample purchased their necessary drugs from their allowance

(Uddin, 2013). This showed from the study’s findings that 94.87% of the poor older people

had met their essential medication with the aid of the allowance (Uddin, 2013).

The impact evaluation of HelpAge International on cash transfers and older people’s access to

healthcare services in four sub-Saharan African countries showed that cash transfer

programmes helped poor older people to access healthcare services (HelpAge International,

2017). The older people in these four countries identified the cost of transportation to health

facilities as hindrance in accessing healthcare services (HelpAge International, 2017).

However, with the cash transfer programmes, most of the beneficiaries were able to access

healthcare services. In Ethiopia, one of the beneficiaries stated: “Through the cash transfer, I

have money for transport to go and seek healthcare services” (HelpAge International, 2017,

p. 21). While in Tanzania, an old recipient of the cash receipt had this to say: “Sometimes

when [the cash transfer] is there, it helps to meet transport costs to the hospital. If the cash

transfer money is there I do not beg – I just use it to go to the health facility”(HelpAge

International, 2017, p. 21)

COPYRIGHT © IAARR: https://www.afrrevjo.net

10

Indexed African Journals Online: www.ajol.info

Indexed Society of African Journals Editors (SAJE); https://africaneditors.org/

AFRREV VOL 14 (1), S/NO 57, JANUARY, 2020

Aside from the use of cash transfers in paying for transport cost to health facilities, older

people in the impact evaluation analysis use cash transfers to pay for hospital bills, treatment

and medicines. In Ethiopia, a male respondent stated: “Without the cash transfer, we would

not be able to access any health services as they are too expensive, even at the health

centre”(HelpAge International, 2017:21). In Mozambique, the cash transfers helped an old

male patient to pay for his medical surgery. According to him:“I had an operation and the

money from the PSSB helped to pay for it”(HelpAge International, 2017, p. 22).

The difference-in-difference estimates in Mexico on the effects of income supplementation on

the health of older people showed that the intervention supported half of the beneficiaries’

visit to a doctor and the number of visits to doctors increased compared to those of non-

beneficiaries (Aguila, Kapteyn, & Smith, 2015). The monthly cash received by the older

people gave a sense of relief to their relatives who were responsible for out-of-pocket (OOP)

spending on healthcare services. The income support helped the older people to pay for their

healthcare expenditure. However, some of them complained of the high cost of drugs (Aguila

et al., 2015). In a similar study also in Mexico, vaccination coverage among cash transfer

beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries stood at 46% and 41% for influenza, 52% and 45% for

pneumococcal disease and 79% and 71% for tetanus respectively. The study analysis showed

that the cash transfer programme exerted a significant impact on immunisation and had an

effect of 0.069 (CI95%: 0.038, 0.096; p < 0.001) on influenza vaccine. Further analysis of the

study revealed that “pneumococcal and tetanus vaccine results were analogous with

coefficient value of 0.0.72 (CI95%: 0.043, 0.102; p <0.001) and 0.066 (CI95%: 0.041, 0.092,

p <0.001), respectively” (Salinas-Rodríguez and Manrique-Espinoza, 2013, p. 5)

Aside from the cash transfer programme making influenza immunisation coverage 7% higher

for beneficiaries of the intervention than those of non-beneficiaries, the intervention increased

the possibility of taking up the complete vaccination schedule (coefficient = 0.055, CI95%:

0.028, 0.028; p < 0.001) (Salinas-Rodríguez & Manrique-Espinoza, 2013).

In the Mexican State of Yucatan, a qualitative interview showed that before the introduction of

non-contributory social pension, one of the beneficiaries of the intervention felt unhappy for

not having money to access healthcare services. However, with the introduction of the

intervention, he was happy for receiving the intervention:

Well, indeed I did not feel sad. I was ashamed because the money was not

enough to buy needed things, and then, when I got sick, I used to have to beg

for money. But now, at least we have some money. If I get sick, at least I

have money to buy medicine that [the health services] don’t have(Salinas-

Rodríguez et al., 2014, p. 6)

In South Africa, the study conducted by Lloyd-Sherlock and Agrawal (2014), on cash

transfers and older people’s health showed mixed effects. The cash transfer programme was

significantly linked with more frequent outpatient visits for beneficiaries of the programme

(OR 1.77; 95% CI1.00-3.15). However, the analysis of the programme did show that rural

setting was not significantly linked with outpatient visits. Nevertheless, the programme was

significantly associated with lower awareness (OR:0.61: 95% ci:0.45-0.82) and the treatment

of hypertension (OR:0.68; 95% CI: 0.49-0.94). On older female beneficiaries, the programme

was associated with healthcare utilisation (OR:1.56; 95% CI: 1.15-2.12), awareness (OR:1.95;

95% CI:1.44-2.64) and treatment (OR:1.86; 95% CI: 1.35-2.57) (Lloyd-Sherlock and

Agrawal, 2014).

COPYRIGHT © IAARR: https://www.afrrevjo.net

11

Indexed African Journals Online: www.ajol.info

Indexed Society of African Journals Editors (SAJE); https://africaneditors.org/

AFRREV VOL 14 (1), S/NO 57, JANUARY, 2020

Discussion

This review is the first to assess the impact of income-support for older people’s health in

developing countries. The findings from the systematic review showed that income-support to

older people helped in improving their anthropometric or nutritional status, cognitive

functions and psychological wellbeing. In addition, income-support allows older people to

access health services which in turn improve their health status.

Income inequality prevents people from both developed and developing countries from

accessing health services when needed. For instance, in the British Columbia, Canada, it was

discovered that people with lower incomes were less likely to access general practitioner (GP)

and specialist services (Penning and Zheng, 2016). In sub-Sahara Africa, studies have shown

that poverty hinders children, women and the vulnerable from accessing healthcare service

when they are indisposed (Aregbeshola& Khan, 2018; Awiti, 2014; Keya et al., 2018; Lanre-

Abass, 2008). Older people are the ones mostly affected by poverty in developing countries,

especially older people without social security or pension benefits (Marmot, 2006). The

prevalence of poverty among older people in developing countries has been responsible for

many governments’ use of income-support for older people.

Our findings showed that income-support improved older people’s anthropometric or

nutritional status in China, Ethiopia and Mexico. Although it had a significant effect in China,

the study did not have the same significant level of effect in Ethiopia, while in Mexico, it had

no significant effect. Nevertheless, there was a significant effect on food security for

beneficiaries of the intervention than non-beneficiaries.

In terms of cognitive functions, only two studies reported positive effects: those in China and

Mexico. While in Mexico, the studies did not present the outcomes of the intervention on the

study sample, it, however, stated that the intervention had a significant impact on a subgroup.

It was possible for the study in China to assess the cognitive functions of older beneficiaries of

the social pension programme through MMSE score. Those who enrolled in the social pension

programme had a 100% increase in income benefit and the income benefit improved their

MMSE score with a significant effect. Income- support has been known to improve the

cognitive functions of beneficiaries through the consumption of variety of diets. In Nicaragua,

beneficiaries that were exposed to cash transfer programme had their cognitive development

raised by 0.09 standard deviations compared to the non-beneficiary group in 2006, and 0.08

standard deviations greater in 2008 (Macours et al., 2012).

Findings from this review also showed that income-support improve the health outcomes and

psychological wellbeing of older people. Data from the three studies that evaluated income-

support and the wellbeing of older people in China, Ethiopia and Mexico revealed that the

beneficiaries of the interventions felt happy because the income-support added value to their

life. Similar studies have revealed the estimated positive effects of income-support on the

wellbeing of beneficiaries in Columbia, Ghana, Kenya and Lesotho (Attah et al., 2016;

Martínez & Maia, 2018; Pereira, 2016).

Aside from the evidence from this review on the positive effects of income-support on the

psychological wellbeing of older people, our findings also showed positive effects of income-

support on older people’s health. From our review, income-support had positive effects on

hypertension awareness, allowed beneficiaries to identify and act on their health needs, and a

reduction in the incidences of hypertension and improved lung functions. However, one study

reported no effect of income-support on self-reported general health in China. Two studies

COPYRIGHT © IAARR: https://www.afrrevjo.net

12

Indexed African Journals Online: www.ajol.info

Indexed Society of African Journals Editors (SAJE); https://africaneditors.org/

AFRREV VOL 14 (1), S/NO 57, JANUARY, 2020

that used systematic reviews to assess the impact of cash transfers on health outcomes showed

strong evidence of cash transfer uptake on the health outcomes of beneficiaries of the

programmes (Lagarde et al., 2009; Pega et al., 2017).

Among the seven studies we reviewed, six assessed the impact of income-support on the

uptake of healthcare services by older people. Our findings showed that income-support

enhanced the uptake of healthcare services when needed. Income-support helped older people

to transport themselves to health facilities, pay for medical services, including the purchase of

medical drugs. Aside from these, one beneficiary was able to use the income-support to pay

for surgery. In Ethiopia, Mozambique, Tanzania and Zimbabwe, the beneficiaries of the

income-support programmes agreed that the income they received was little, but most of them

were able to use the little income to access healthcare services. Similar studies have been able

to prove the positive effects of income support on the uptake of healthcare services (see

Lagarde et al., 2009; Pega et al., 2017).

Our findings have been able to prove the positive effects of income-support on the health of

older people in developing countries. These findings are in consonance with the findings of

similar studies in the United States. Data provided by the Gregory Armstrong of the Centres of

Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the study of Arno et al (2011), supported their

hypothesis that income-support programme had a beneficial impact on the health of older

people in the United States. In a similar vein, an income-support programme, Earned Income

Tax Credit (EITC), was reported to have had a positive impact on the health of Americans

(Arno et al.,2009).

There are some limitations that this review encountered. Firstly, because older people face a

lot of challenges, especially in developing countries where there are limited social protection

schemes to support them, data on the impact of income-support on older people’s health were

very scarce. Consequently, of the selected studies for this review, only seven met our inclusion

criteria. Secondly, our search for relevant literature was limited to studies conducted in

English; whereas, there are various studies on social protection for the elderly in Latin

America conducted in other languages. Finally, in some of the studies included in this review,

we discovered missing data that might have been helpful in our analysis.

Conclusion

This systematic review is the first to assess the impact of income-support on older people’s

health in developing countries. Our analysis showed that income-support to poor older people

improved their health and wellbeing. Although income-support are meant to support older

people in various aspect of their lives, our analyses was limited to older people’s health.

The limitations of this review make it mandatory for further research on the subject area.

Nevertheless, our findings have implications for healthcare policies in developing countries. It

has been proved that income inequality hinder access to healthcare services among the

vulnerable. Governments in developing countries need the political will to design and

implement social health insurance programmes that will have access to healthcare service to

all irrespective of socioeconomic status.

Our systematic review findings have shown that social protection mechanisms address the

exclusion and vulnerability of older people. This current evidence supports the relevance of a

life-course mechanism to ageing and the calls for improving and protecting older people

against social exclusion in the implementation of SDGs.

COPYRIGHT © IAARR: https://www.afrrevjo.net

13

Indexed African Journals Online: www.ajol.info

Indexed Society of African Journals Editors (SAJE); https://africaneditors.org/

AFRREV VOL 14 (1), S/NO 57, JANUARY, 2020

References

Aboderin, I. A. G., & Beard, J. R. (2015). Older people’s health in sub-Saharan Africa. The

Lancet, 385(9968), e9–e11. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61602-0

Aguila, E., Kapteyn, A., & Smith, J. P. (2015). Effects of income supplementation on health

of the poor elderly: The case of Mexico. Proceedings of the National Academy of

Sciences of the United States of America, 112(1), 70–75.

https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1414453112

Aregbeshola, B. S., & Khan, S. M. (2018). Out-of-pocket payments, Catastrophic health

expenditure and poverty among households in Nigeria 2010. International Journal of

Health

Policy

and

Management,

7(9),

798–806.

https://doi.org/10.15171/ijhpm.2018.19

Arno, P. S., House, J. S., Viola, D., & Schechter, C. (2011). Social security and mortality:

The role of income support policies and population health in the United States.

Journal of Public Health Policy, 32(2), 234–250. https://doi.org/10.1057/jphp.2011.2

Arno, P. S., Sohler, N., Viola, D., & Schechter, C. (2009). Bringing health and social policy

together: The case of the earned income tax credit. Journal of Public Health Policy,

30(2), 198–207. https://doi.org/10.1057/jphp.2009.3

Aromataris, E., & Munn, Z. (Eds.) (2017). Chapter 1: JBI systematic reviews. Retrieved 23

October

2019,

from

https://wiki.joannabriggs.org/display/MANUAL/Chapter+1%3A+JBI+Systematic+R

eviews

Attah, R., Barca, V., Kardan, A., MacAuslan, I., Merttens, F., & Pellerano, L. (2016). Cash

transfers and psychosocial well-being: Evidence from four African countries (No.

333). Retrieved from International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth website:

https://ideas.repec.org/p/ipc/opager/333.html

Audain, K., Carr, M., Dikmen, D., Zotor, F., & Ellahi, B. (2017). Exploring the health status

of older persons in Sub-Saharan Africa. The Proceedings of the Nutrition Society,

76(4), 574–579. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0029665117000398

Awiti, J. O. (2014). Poverty and health care demand in Kenya. BMC Health Services

Research, 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-014-0560-y

Cheng, L., Liu, H., Zhang, Y., & Zhao, Z. (2018). The health implications of social pensions:

Evidence from China’s new rural pension scheme. Journal of Comparative

Economics, 46(1), 53–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2016.12.002

Dugarova, E. (2017). Ageing, older persons and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable

Development. UNDP.

COPYRIGHT © IAARR: https://www.afrrevjo.net

14

Indexed African Journals Online: www.ajol.info

Indexed Society of African Journals Editors (SAJE); https://africaneditors.org/

AFRREV VOL 14 (1), S/NO 57, JANUARY, 2020

HelpAge International. (2017). Cash transfers and older people’s access to healthcare: A

multicounty study in Ethiopia, Mozambique, Tanzania and Zimbabwe. Retrieved from

http://www.helpage.es/silo/files/cash-transfers--.pdf

Hong, Q. N., Pluye, P., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., … Vedel, I.

(2018). Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) VERSION 2018. McGill University,

Department of Family Medicine.

Keya, K. T., Sripad, P., Nwala, E., & Warren, C. E. (2018). ‘Poverty is the big thing’:

Exploring financial, transportation, and opportunity costs associated with fistula

management and repair in Nigeria and Uganda. International Journal for Equity in

Health, 17(1), 70. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-018-0777-1

Lagarde, M., Haines, A., & Palmer, N. (2009). The impact of conditional cash transfers on

health outcomes and use of health services in low- and middle-income countries.

Cochrane

Database

of

Systematic

Reviews.

https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008137

Lanre-Abass, B. A. (2008). Poverty and maternal mortality in Nigeria: Towards a more viable

ethics of modern medical practice. International Journal for Equity in Health, 7, 11.

https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-7-11

Lloyd-Sherlock, P., & Agrawal, S. (2014). Pensions and the health of older people in South

Africa: Is there an effect? The Journal of Development Studies, 50(11), 1570–1586.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2014.936399

Macours, K., Schady, N., & Vakis, R. (2012). Cash transfers, behavioral changes, and

cognitive development in early childhood: Evidence from a randomized experiment.

Applied Economics, 4(2), 27.

Marmot. (2006). Health in an unequal world. Lancet (London, England), 368(9552), 2081–

2094. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69746-8

Martínez, D. M., & Maia, A. G. (2018). The impacts of cash transfers on subjective wellbeing

and poverty: The case of Colombia. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 39(4),

616–633. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-018-9585-4

Nanyonjo, A. (2016, December 16). Long Term care systems for older adults in sub-Saharan

Africa: Are new approaches needed? Retrieved 22 October 2019, from IHP website:

https://www.internationalhealthpolicies.org/blogs/long-term-care-systems-for-older-

adults-in-sub-saharan-africa-are-new-approaches-needed/

Pega, F., Liu, S. Y., Walter, S., Pabayo, R., Saith, R., & Lhachimi, S. K. (2017).

Unconditional cash transfers for reducing poverty and vulnerabilities: Effect on use of

health services and health outcomes in low- and middle-income countries. Cochrane

Database of Systematic Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011135.pub2

COPYRIGHT © IAARR: https://www.afrrevjo.net

15

Indexed African Journals Online: www.ajol.info

Indexed Society of African Journals Editors (SAJE); https://africaneditors.org/

AFRREV VOL 14 (1), S/NO 57, JANUARY, 2020

Penning, M. J., & Zheng, C. (2016). Income inequities in health care utilization among Adults

aged 50 and older. Canadian Journal on Aging = La Revue Canadienne Du

Vieillissement, 35(1), 55–69. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980815000562

Pereira, A. (2016). Cash transfers improve the mental health and well-being of youth:

Evidence from the Kenyan cash transfer for orphans and vulnerable children.

UNICEF.

Salinas-Rodríguez, A., & Manrique-Espinoza, B. S. (2013). Effect of the conditional cash

transfer program Oportunidades on vaccination coverage in older Mexican people.

BMC International Health and Human Rights, 13, 30. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-

698X-13-30

Salinas-Rodríguez, A., Torres-Pereda, Ma. D. P., Manrique-Espinoza, B., Moreno-Tamayo,

K., andTéllez-Rojo Solís, M. M. (2014). Impact of the non-contributory social

pension Program 70 y más on Older Adults’ Mental Well-Being. PLoS ONE, 9(11).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0113085

Uddin, A. (2013). Social safety nets in Bangladesh: An analysis of impact of old age

allowance

program

(BRAC

University).

Retrieved

from

https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/61804718.pdf

United Nations. (2014). World economic situation and prospects. Retrieved from

https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/policy/wesp/wesp_current/2014wesp_count

ry_classification.pdf

United Nations. (2016). Sub-Saharan Africa’s growing population of older persons. Retrieved

from

https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/popfacts/PopFa

cts_2016-1.pdf

COPYRIGHT © IAARR: https://www.afrrevjo.net

16

Indexed African Journals Online: www.ajol.info

Indexed Society of African Journals Editors (SAJE); https://africaneditors.org/